AI agents and the 90% problem

Useful AI agents are still limited by their reliability on real-world tasks. But Chinese AI agents are pushing the limit.

Today’s top AI models are mind-blowingly good at certain tasks. They can achieve gold-level performance on the International Math Olympiad. They can beat out all but the best human programmers on coding tests. Math and science benchmarks are quickly getting saturated. And yet, where is the AI revolution we were promised?

2025 was supposed to be the year of agents. Autonomous online systems with the ability to book flights, plan your next trip, schedule appointments, and complete mundane paperwork were supposed to finally prove the real-world transformative effects of generative AI. On paper, AI models are getting really good at agentic tasks, with ever more sophisticated tool-calling capabilities over increasingly long time horizons.

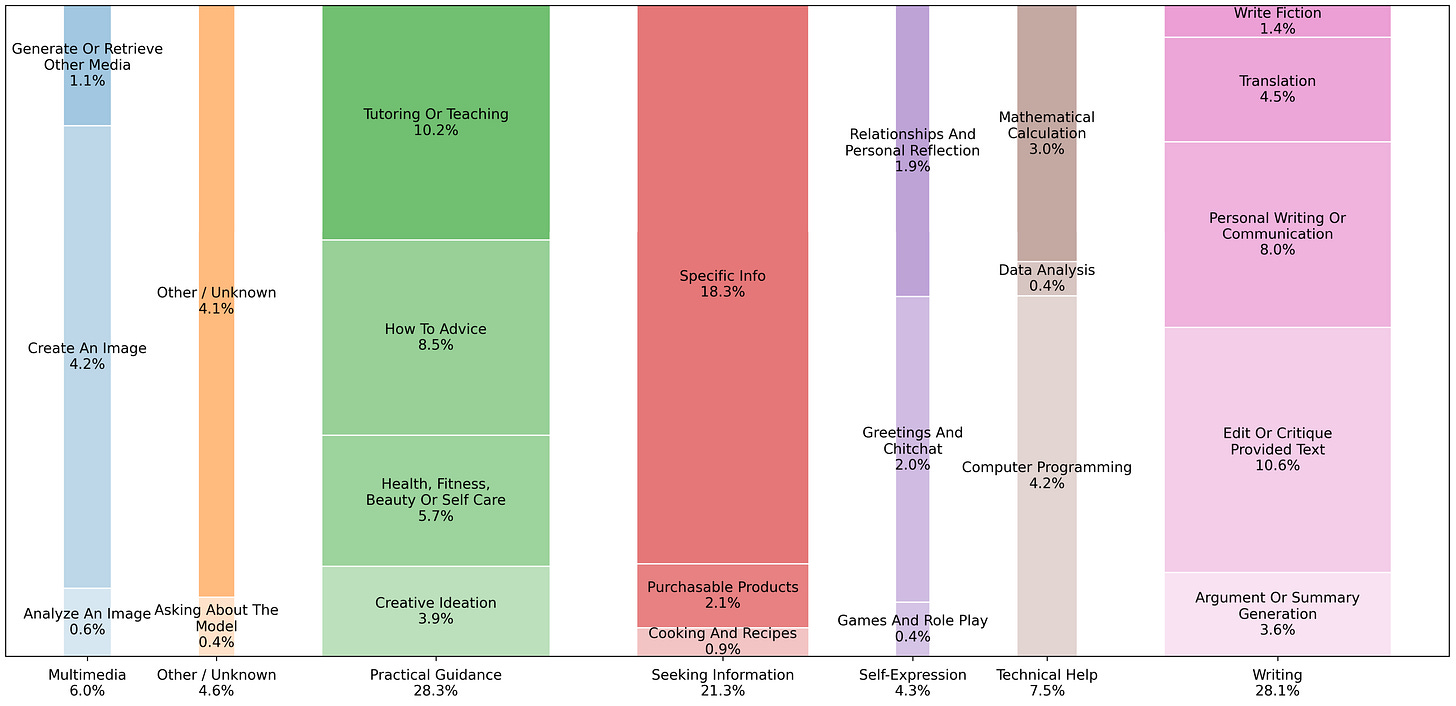

But when we look at how AI is really being used, it’s still relatively limited. A recent study (below) revealed that ChatGPT is still mostly being used for very basic stuff, like personal advice and text editing. And much-hyped agentic AI browsers like ChatGPT Atlas and Perplexity’s Comet don’t seem to be catching on, perhaps due to their mediocre performance.

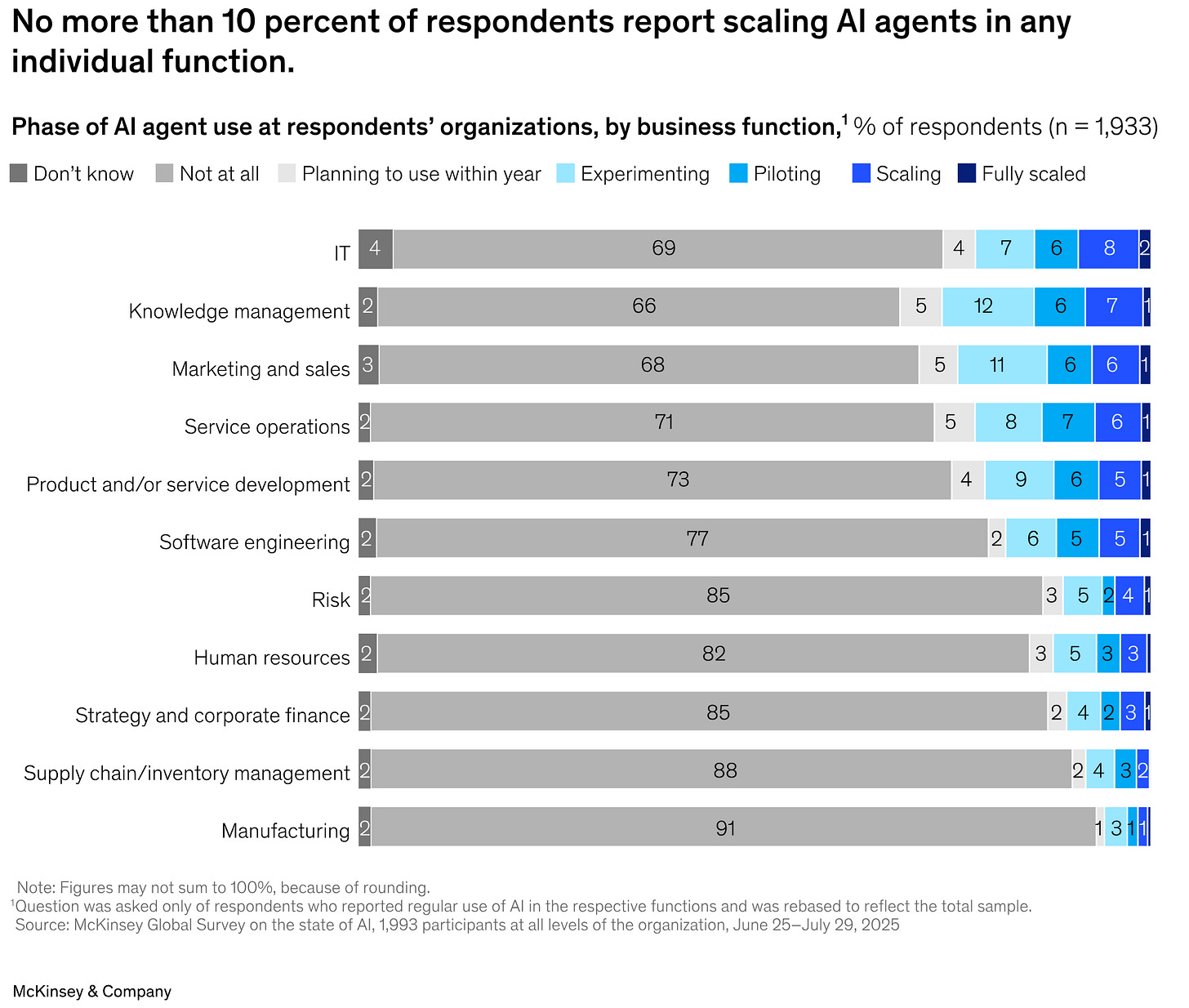

There’s a similar story for business users. When you look at the set of “1,001 AI use cases from Google Cloud customers,” it’s still mostly customer service agents and marketing content. Klarna, a fintech startup, made headlines in 2024 for announcing it was using AI agents to do the work of 700 customer service reps only to make headlines again in May 2025 for reversing course and moving back to human customer service, citing “lower quality” from AI agents. A recent McKinsey survey found that while many businesses are experimenting with AI agents, very few are deploying them at scale.

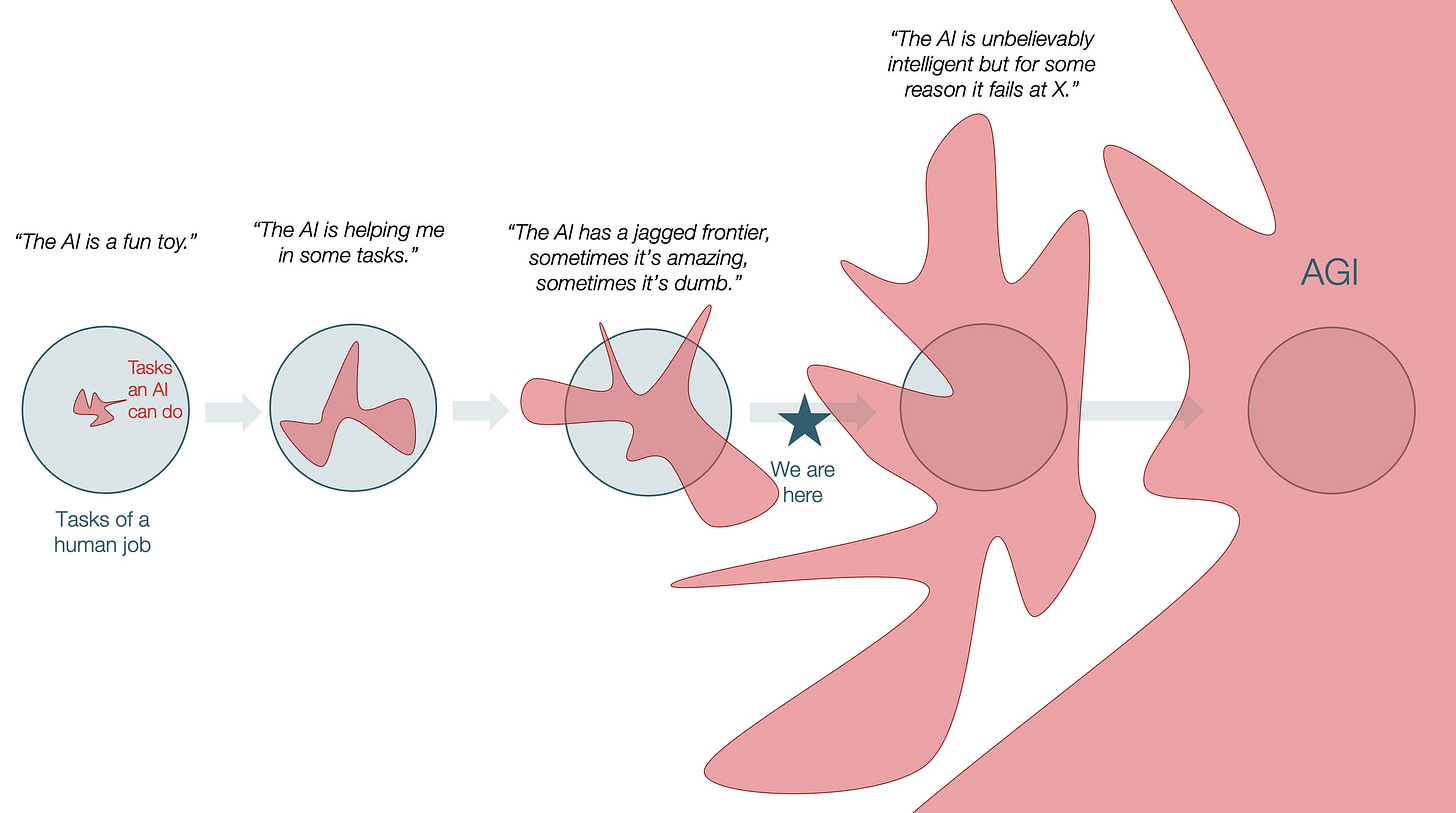

In some very specialized areas, AI is incredible and already proving to be transformative: coding, protein folding, self-driving cars. But many AI legends like Ilya Sutskever, Yann LeCun, and Andrej Karpathy believe that true general intelligence is still a long way away. In some ways, the kind of “jagged” intelligence we’re seeing now with AI is nothing new. Traditional computers have long had superhuman capabilities in some areas, like flawless calculation and memory, while being extremely dumb at most other things. Will scaling up LLMs ultimately take us from narrow to broad superhuman intelligence?

The 90% problem

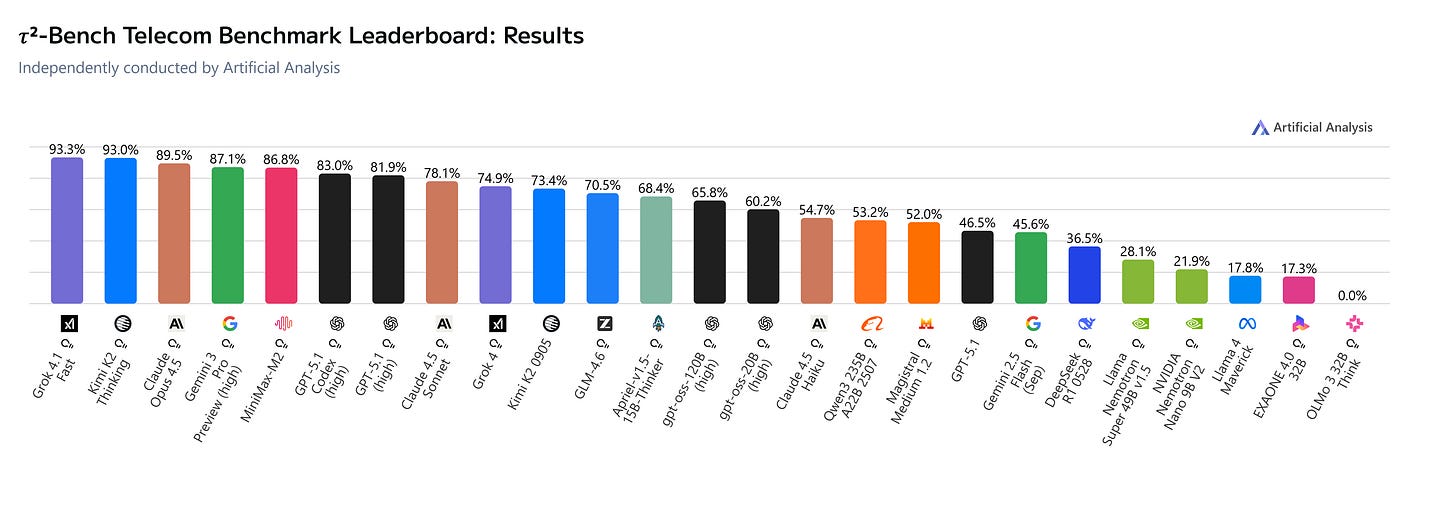

While AI systems are impressive in some domains, their usefulness in actually getting things done is limited by their unreliability. This is captured by benchmarks that test AI agentic capabilities on real-world tasks. On the OSWorld benchmark, top AI models are only able to achieve a 63% success rate on basic tasks. On 𝜏²-bench, which tests AI agents on troubleshooting a real-world telecom customer issue, top AI models score around the 90% level at the highest end.

When I started working in management consulting after college, a partner explained to a bunch of us new analysts that getting a B+ or an A- might be acceptable in school, but in the real world everything had to be A+ work. This principle also applies to AI agents. It’s not enough that an AI agent gets us the right flight booking or makes the right hotel reservation 90% of the time. With such a high error rate, it’s more work to verify and redo the agent’s work. Like working with a new intern, many times it’s easier just to do the task yourself and know that it’s done right. On top of all this, there’s a risk that an AI agent might not just do something wrong but something bad, and for businesses that could create security risks.

This reliability problem helps to explain why we’ve seen such limited AI agentic capabilities in areas like smartphones. Apple has gotten a lot of flak for being slow to add AI features to the iPhone. So far, we have Siri providing summaries of emails and custom emojis—nothing earth-shattering. Apple has delayed the rollout of real AI agentic features due to an “error rate” that was still “unacceptable.”

But it’s not just Apple. Other major smartphone makers have been slow to release true AI agentic features. Samsung’s Galaxy series gives you live AI transcriptions for voice recordings. Google’s Pixel 10 has “Magic Cue,” which proactively searches across multiple apps to offer suggestions. These are fun features but hardly the kinds of deeply integrated, cross-app agentic capabilities that would really transform how we use our phones. (I’ll get to Chinese smartphones in a minute.)

It also helps to explain the lack of full-blown AI capabilities for smart home devices, such as Amazon’s Alexa devices. The old, hard-coded method for voice-activated lights or thermostat controls was reliable enough to be useful. But the shift to generative AI and LLMs has so far proven too much of a sacrifice in reliability to be rolled out to smart home devices at scale. Recent reviews of Amazon’s attempt to infuse LLMs into Alexa devices, known as Alexa+, have been critical for taking a step backwards on reliability for basic tasks.

Binary vs. nonbinary tasks

The problem can be boiled down to the difference between two kinds of tasks: binary and nonbinary.

Binary tasks are ones where you either fully complete the task or you don’t. Some of these tasks might be challenging, like safely driving a car to a destination. And some of these tasks might be simple, like ordering food delivery. But it’s hard for AI systems to be useful at these binary tasks because even if they’re quite good, they might not be good enough that we can really let our guard down and trust them to finish the job.

What counts as “good enough”? The degree of accuracy or reliability required depends on factors like the cost of failure and the availability of alternatives. In a recent Dwarkesh podcast interview, Andrej Karpathy talked about the “march of nines,” drawing on his experience leading Tesla’s autonomous driving program. Each additional “9” in an AI system’s degree of reliability is increasingly difficult to earn as you try to handle increasingly rare and complex edge cases. Because the cost of failure is so high with self-driving cars—i.e., a car accident—the minimum level of system reliability for these systems has to be not just 90% or 99% or even 99.9% but many “9s.” But even for mundane tasks like ordering food delivery, the bar for reliability has to be fairly high to beat out simply placing the order yourself.

Nonbinary tasks, in contrast, are ones where you can get closer and closer to completion or do the task better and better until you have a result that’s basically good enough. Rather than an all-or-nothing outcome, every extra bit of progress or improvement is useful. This is where we see most of the use-cases for AI and AI agents today. An AI agent that can get us most of the way to coding up a functioning website or drafting a legal contract is very useful. But it still relies on humans to complete that last mile of work and quality control.

Further improvements on these types of nonbinary tasks by AI may lead to a kind of “bunching” of human roles at the high-end of the spectrum, increasing demand for top-notch human expertise and judgment. Geoffrey Hinton, who would later win a Nobel Prize for his work on AI, famously said in 2016 that “we should stop training radiologists now” because the job would be taken over by AI. But the demand for radiologists has only grown since then with average salaries reaching $498,000 in 2024. Radiologists use AI tools to do their jobs better, and this has only seemed to make radiologists more valuable, not less.

Economists like David Autor and Daron Acemoglu have studied the “polarized” effects of new technology on the labor force. Some technologies like automated grocery checkout stands or autonomous vehicles are “labor-substituting,” meaning they replace workers. But other kinds of technology are “labor-augmenting,” like surgical robots or Excel spreadsheets, making certain kinds of workers even more valuable. While it’s not clear how much AI agents will really replace human workers for binary tasks (except driving and delivery), it is likely that rapid AI progress on nonbinary tasks will increase demand for the very high-end of human expertise and judgment.

AI agents in China

In some ways, AI use-cases in China today look similar to the US. AI chatbots like ByteDance’s popular Doubao app and DeepSeek can provide personal advice or generate funny videos to post on social media. When you do a search on Baidu or Alibaba’s Amap, you can get AI-powered search results. Creators and livestreamers use AI to edit content and even launch virtual sales avatars.

But in other ways, China seems to be moving faster on rolling out AI agents, particularly in smartphones. ByteDance and Huawei in particular are pursuing two different approaches to AI agents on smartphones.

ByteDance’s Doubao smartphone

ByteDance recently released a new AI-powered smartphone made with ZTE called the Nubia M153. The smartphone has voice-activated, cross-app agentic capabilities powered by ByteDance’s Doubao AI assistant. Just by speaking to the phone, you can have it book a flight or post a message to a group chat or even open the Tesla app and use it to open the car trunk. The phone seems to go through a process similar to OpenAI’s agent where it takes many screenshots of your phone over time, analyzes each screenshot, and then decides where to scroll or tap. Before making any purchase or booking, it asks for user confirmation.

While I haven’t tried the phone myself, my WeChat and Xiaohongshu feeds have been flooded with excited reviews. ByteDance’s new AI agent phone sold out within days of its launch. Taylor Ogan, an American VC based in Shenzhen, has posted several videos showing off the phone’s agentic capabilities and called it “another DeepSeek moment.”

At the same time, ByteDance’s new smartphone is already running into access issues with popular apps like WeChat, Alipay, and Pinduoduo. When ByteDance’s AI agent tries to use these apps, it seems to trigger an automatic block, although it’s also likely that major app makers simply don’t want to give ByteDance’s AI agent direct control over their apps. This is probably a sign of a major battle to come between AI agents and app developers, as Poe Zhao of Hello China Tech has written about.

Huawei’s HarmonyOS 6

Huawei is taking a different approach to AI agent-powered smartphones with its latest HarmonyOS 6 mobile operating system. Rather than having an agent take over the phone and operate apps like a human user, Huawei’s Xiaoyi 小艺 agent works with other agent apps in the HarmonyOS ecosystem. These apps are made by other tech companies that have formally partnered with Huawei to grant access and build integration through Huawei’s agent framework. The video below shows how Huawei’s voice-activated Xiaoyi smartphone agent works across these agent apps.

Huawei’s approach is slower than ByteDance’s because Huawei has to build partnerships with each app developer and convince them to integrate with Huawei’s agent framework. But it has the benefit of having formal permission and streamlined integration for the apps that do choose to partner. So far, these partners include some big names like e-commerce giant JD.com, podcasting platform Ximalaya, event ticketing service Damai, and travel site Ctrip. But notably missing are China’s most popular apps like WeChat and Alipay. The big question is whether China’s most powerful app developers will ever allow Huawei or other smartphone makers to operate their apps through AI agents. If not, this would severely limit the usefulness of Chinese smartphone agents.

Will 2026 be the year of agents?

Chinese tech firms like ByteDance and Huawei seem willing to roll out AI agentic capabilities more quickly than their American counterparts. Xiaomi is also gearing up for a major rollout of agentic capabilities across its vast ecosystem of smartphones and smart home devices. Are Chinese AI agents actually good enough to be useful or are they rushing in where US tech firms are being more prudent and cautious? Will China’s faster implementation give it an edge with AI agents or will it backfire by turning off users with a buggy and unreliable experience? For now, Chinese tech firms seem to believe there’s only one way to find out. And if they’re successful, this will put greater pressure on American tech firms to respond with their own agentic rollout. ■

The binary vs nonbinary task distinction you draw here is really sharp and explains so much about why agents haven't taken off yet. Most companies are throwing agents at nonbinary tasks where they can be helpful but still need oversight, while users expect agents to nail binary tasks like booking flights or scheduling meetings, which demands near perfection. What's intresting is that China's willingness to ship imperfect agents might actually create a feedback loop where rapid iteration leads to faster improvement, even if the intial experience is rougher. Your radiologist example perfecty captures how AI can make experts more valuable rather than replacing them

Yes figuring out which "last mile" problems to solve and which to ignore is the challenge ahead.