Does China care about AGI?

Chinese tech leaders and researchers talk openly about AGI. But Chinese policymakers don't seem focused on the "race to AGI" like in the US.

Across many emerging technologies—quantum, fusion, space, etc.—Chinese and American policymakers share similar views on what’s at stake, even if their approaches to developing these technologies may differ. But on AI, arguably the most consequential technology of all, it’s puzzling how much of a divergence there is between Beijing and Washington. While they both agree on the incredible importance of AI, Beijing seems not to care about the so-called “race to AGI,” or artificial general intelligence.

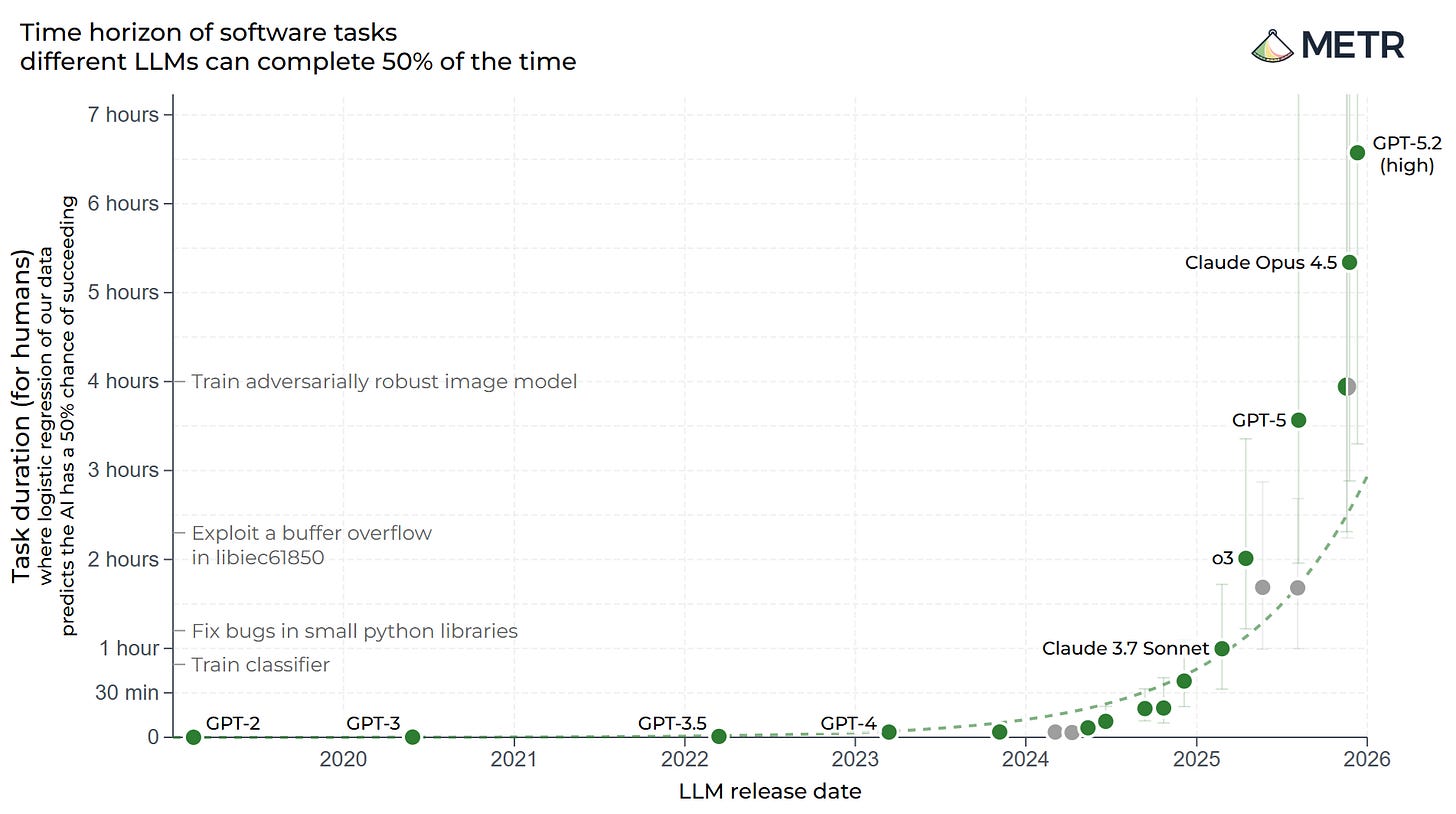

In the US, the idea that AGI could be fast-approaching is a powerful driver behind stock market valuations, massive data center spending, policy decisions, and a large degree of societal angst. Specifically, there’s this idea that we may soon reach an inflection point where AI systems become recursively self-improving, leading to an “intelligence explosion” that would utterly transform every domain of life from military affairs to the entire economy.

Within the Washington policy community, including key officials under the Biden administration, there’s a “race to the bomb” logic vis-à-vis China: if China gets to AGI before the US, it would completely upend the balance of power between the two countries. This later became a key rationale for US export controls on advanced AI chips to China.

The missing AGI in China’s AI policies

But Beijing doesn’t seem focused on AGI.

In 2017, after DeepMind AlphaGo’s stunning defeat of the world’s best human Go player the year before, China launched its ambitious “Next-Generation AI Development Plan.” This plan only mentions promoting research on “data-driven AGI mathematical models and theories” (“数据驱动的通用人工智能数学模型与理论”) once in passing.

China’s recent “AI+” initiative focuses on applications and adoption but makes no direct reference to AGI. Last year, at a special Politburo study session on AI, Xi Jinping stressed the importance of AI as a “strategic technology that will lead a new round of scientific and technological revolution and industrial transformation” (人工智能作为引领新一轮科技革命和产业变革的战略性技术) but did not mention AGI.

The few Chinese policy documents and official texts that do reference AGI seem to be talking about a different translation of the term in Chinese (通用人工智能) that’s more like “general-purpose AI” rather than AGI as commonly understood in the US. As a ChinaTalk piece noted, the term “AGI” (“通用人工智能”) was used in the readout for a 2023 Politburo meeting led by Xi Jinping but was later clarified in a follow-up People’s Daily article as meaning “general AI” as opposed to “specialized AI” (专用人工智能) that’s only designed for specific tasks.

From the 2023 People’s Daily article, titled “Focusing on General AI Development” (重视通用人工智能发展):

AI can be divided into specialized AI and general AI. Specialized AI can only complete specific tasks using a particular set of algorithms. General AI, also known as strong AI, can generalize and make inferences in a human-like way. For example, it can receive and integrate different categories of data of a certain scale—including text, images, and speech—and when faced with a new task, it can quickly “recall” related experiences and apply the relevant knowledge it has mastered to creatively solve problems and complete tasks.

人工智能可分为专用人工智能和通用人工智能。专用人工智能,只能通过一套特定的算法,完成特定的任务。通用人工智能又称强人工智能,能像人一样举一反三、触类旁通。比如,它能接收不同类别、有一定规模的数据,包括文字、影像、语音,然后把它们融合在一起,遇到新任务时,就可以快速“想到”做过的相关事情并调用掌握的相关知识,创造性地解决问题、完成任务。

Some local governments have also released AI policy documents that use the term 通用人工智能, such as the Beijing municipal government’s 2023 “Several Measures to Promote the Innovative Development of General-Purpose AI in Beijing” (北京市促进通用人工智能创新发展的若干措施). But again, their use of the Chinese term for AGI sounds more like “general AI” and hardly differs from discussions of regular AI. The terms AI and AGI seem almost interchangeable. They talk about the same general support for compute infrastructure, data, foundational models, and applications—not a radical transformation of society.

Chinese tech leaders aim for AGI

The puzzle only deepens when you consider the fact that many of China’s top AI leaders in the private sector do talk openly about pursuing AGI—and quite frequently.

DeepSeek’s founder Liang Wenfeng 梁文锋 said in a 2024 interview, “Our destination is AGI,” using the English acronym (“我们目的地是AGI”). In a recent podcast interview, Zhipu’s CEO Zhang Peng 张鹏 said, “Zhipu wasn’t founded simply as a company to make money. Our original goal is to explore what AGI ultimately is.” (“智谱其实不是单纯地说我们就是想成立个公司去赚钱。其实本源还是在于我们要去探索AGI到底是什么。”) Moonshot’s founder Yang Zhilin 杨植麟 said he literally named his company because he wanted to do a “moonshot” mission to reach AGI.

In another recent podcast interview, MiniMax’s founder Yan Junjie 闫俊杰 explained how his company was taking a multimodal approach to reaching AGI. Yan Junjie was also invited to a meeting with Chinese Premier Li Qiang earlier this year, just weeks after MiniMax listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

Perhaps most striking was Alibaba CEO Eddie Wu’s 吴泳铭 25-minute presentation (Chinese / English) last fall on his company’s path to AGI and even ASI, or artificial superintelligence. Lest there be any doubt about what he means by AGI or 通用人工智能, he spells out everything clearly, including the emphasis on “iterative self-improvement”:

We see the realization of AGI—an intelligent system with human-level general cognitive abilities—as something that the industry now regards as a matter of certainty. However, we believe AGI is not the endpoint of development but a completely new starting point. AI will certainly not stop at AGI; it will move toward artificial superintelligence that surpasses human intelligence and is capable of iterative self-improvement, what the industry calls ASI.

我们看到实现AGI一个具备人类通用认知能力的智能系统现在在行业看来已经成为确定性的事件。然而我们觉得AGI并非是发展的终点,而是全新的起点。AI肯定不会止步于AGI,它将迈向超越人类智能,能够自我迭代进化的超级人工智能,行业称为ASI的系统。

Earlier this year, there was even a public discussion at Tsinghua University literally called the AGI-Next Frontier Summit (“AGI-Next 前沿峰会”) where several top Chinese AI leaders talked about the development of AGI. (This broader convergence in how AGI is talked about among Chinese and American tech leaders has been analyzed by Afra Wang and Grace Shao.)

Why is Beijing not focused on AGI?

So why aren’t Chinese policymakers obsessed with AGI like the US or even their own tech leaders?

First, there’s still a lot of uncertainty in China about the pace of technological progress and whether today’s technological paradigms can get us all the way to AGI. Among US tech leaders, there’s a strong belief in “scaling laws,” or the idea that adding more compute to today’s current transformer-based LLM architectures will get us to AGI.

Last year, Anthropic’s CEO Dario Amodei said that AI could wipe out half of all entry-level white-collar jobs in one to five years. Just this month, Microsoft’s AI chief Mustafa Suleyman predicted most white-collar work “will be fully automated by an AI within the next 12 to 18 months.” (To be sure, there are prominent Western AI researchers who are more skeptical of these rapid timelines, such as Yann LeCun and Andrej Karpathy.)

But when Chinese tech leaders talk about AGI, they don’t give the shockingly fast timelines that their American counterparts do. Chinese policy documents talk about timelines for AI adoption and diffusion but not about AI capabilities reaching some explosive takeoff point in the near future.

To be sure, there is some discussion of AI’s potential impact on jobs and how to address this, such as a recent article in Qiushi 求是. And a senior researcher at DeepSeek did offer a rare warning last year that AI could take over human work in the next 10-20 years. But Chinese official statements generally don’t convey any expectation that AGI might be just around the corner.

Second, even when AGI is discussed in China, it doesn’t have the winner-take-all framing that it tends to have in the US. In US discussions, especially around military power, there’s often a worry that whichever nation achieves AGI first will have an insurmountable advantage over everyone else. In China, there seems to be a view that even if the US reaches AGI first, China can quickly catch up and even overtake it.

At the AGI-Next summit, Yao Shunyu 姚顺雨, who Tencent recently poached from OpenAI to become their new chief AI scientist, argued: “History shows that once a technical path is validated, Chinese teams can rapidly replicate and even outperform in specific areas—look at EVs or manufacturing.” Another speaker at the summit, Yang Qiang 杨强, argued: “Let’s look at the history of the internet. It started in the U.S., but China quickly caught up and led in consumer applications—WeChat is a world-class example. AI is similar—it’s a tool, and Chinese ingenuity will push it to the limit.”

Third, Chinese policymakers seem to treat AI not as an existential rupture in human history but as a powerful, general-purpose technology like electricity, computers, or the internet that can turbocharge many other domains: manufacturing, scientific research, services, defense, healthcare and medicine, and so on. Indeed, China’s AI+ initiative shares many parallels with China’s 2015 “Internet+” initiative where the goal was to boost adoption and use this new technology to drive progress across a whole range of areas, from industry to public services.

Nobody “won” the internet. Instead, the question was: who can make the most of this new technology over the long run? While China may see AI as more significant than previous technologies, Beijing’s approach to AI lines up with a longer pattern of trying to harness new cross-cutting technologies through a broader process of economic and social transformation: “informatization” 信息化, “digitization” 数字化, and “intelligentization” 智能化.

Is Beijing secretly racing towards AGI?

How do we know Beijing isn’t secretly sprinting toward AGI? What if they’re hiding their true goals from the public and quietly pursuing a Manhattan Project-style AGI program?

First, it’s important to point out that Chinese official documents and statements have talked about AGI or 通用人工智能 openly. As mentioned earlier, there was the 2023 Politburo study session on AI and subsequent People’s Daily article. Multiple local governments have publicly used the term 通用人工智能 in official documents. Last month, the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT, 信通院), a prominent state-run think tank under the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT, 工信部), just published an AI development research report that talks explicitly about AGI.

There are also local state-run AGI labs. There’s the Beijing Institute for General Artificial Intelligence (BIGAI, 北京通用人工智能研究院) founded by Song-Chun Zhu 朱松纯, a former star AI researcher at UCLA, that is explicitly dedicated to pursuing brain-inspired approaches to achieving AGI. There’s the Chongqing Institute for General AI (重庆通用人工智能研究院). The University of Science & Technology of China in Hefei just launched a new “AGI Research Center” (中国科学技术大学通用人工智能研究所). And if Beijing really wanted to hide language about AGI, they would probably try to stop Chinese AI leaders in the private sector from using this term so often publicly.

But more important than words, there are concrete actions that serve as indicators for whether Beijing is racing to AGI:

Balancing between domestic and imported AI chips. If Beijing were sprinting towards AGI, they would have jumped more quickly to allow the import of as many Nvidia H200 chips as possible. Instead, Beijing has been cautiously trying to find a balance between allowing the import of some AI chips from the US and supporting China’s own domestic chip industry.

No rush to centralize compute. China is trying to develop a “Nationwide Integrated Compute Network” (全国一体化算力网络). But as Liu Liehong 刘烈宏, the head of China’s National Data Administration explains in a Qiushi commentary, this is a long-term project aimed at trying to rationalize and optimize fragmented compute resources across the country, particularly as China builds data centers in inland provinces as part of the “Eastern Data, Western Computing” 东数西算 project. At this point, there are no signs that Beijing is taking over data centers from Chinese hyperscalers like Alibaba and Tencent to create a fully centralized compute system.

Open-source vs. closed-source. If Beijing were racing to AGI, we would expect to see a policy shift toward closed-source models to protect China’s strategic advantage. Instead, we see Beijing heavily promoting open-source as a strategy for driving the adoption of Chinese AI models within China and around the world. Leading Chinese AI labs continue to release open-source versions of their most powerful models.

Should Beijing suddenly shift posture on these key indicators, then we might want to take notice. But for now, Beijing’s words and actions don’t support any all-out, state-driven rush to reach AGI.

There’s an understandable tendency in Washington to project our own ideas and attitudes onto Beijing. If the US is racing to AGI, then surely China must be doing the same thing. But it’s useful to take a step back and see how much of an outlier the US is here. It seems like Beijing’s attitude toward AI as a powerful technology but not a fundamental break with history is more in line with how much of the rest of the world sees it.

US tech mafia wants AGI for wrong reasons

to tokenize and cut employment