India needs a national bullet train system

Thinking big about infrastructure, climate, and economic development with some data and lessons from China's high-speed rail system.

The case for an Indian national high-speed rail (HSR) system

India is the perfect country for a national high-speed rail (HSR) system. The most obvious reasons are India’s high population density, the geographic proximity of its megacities (some of which are the largest cities in the world), and its rapidly growing middle class.

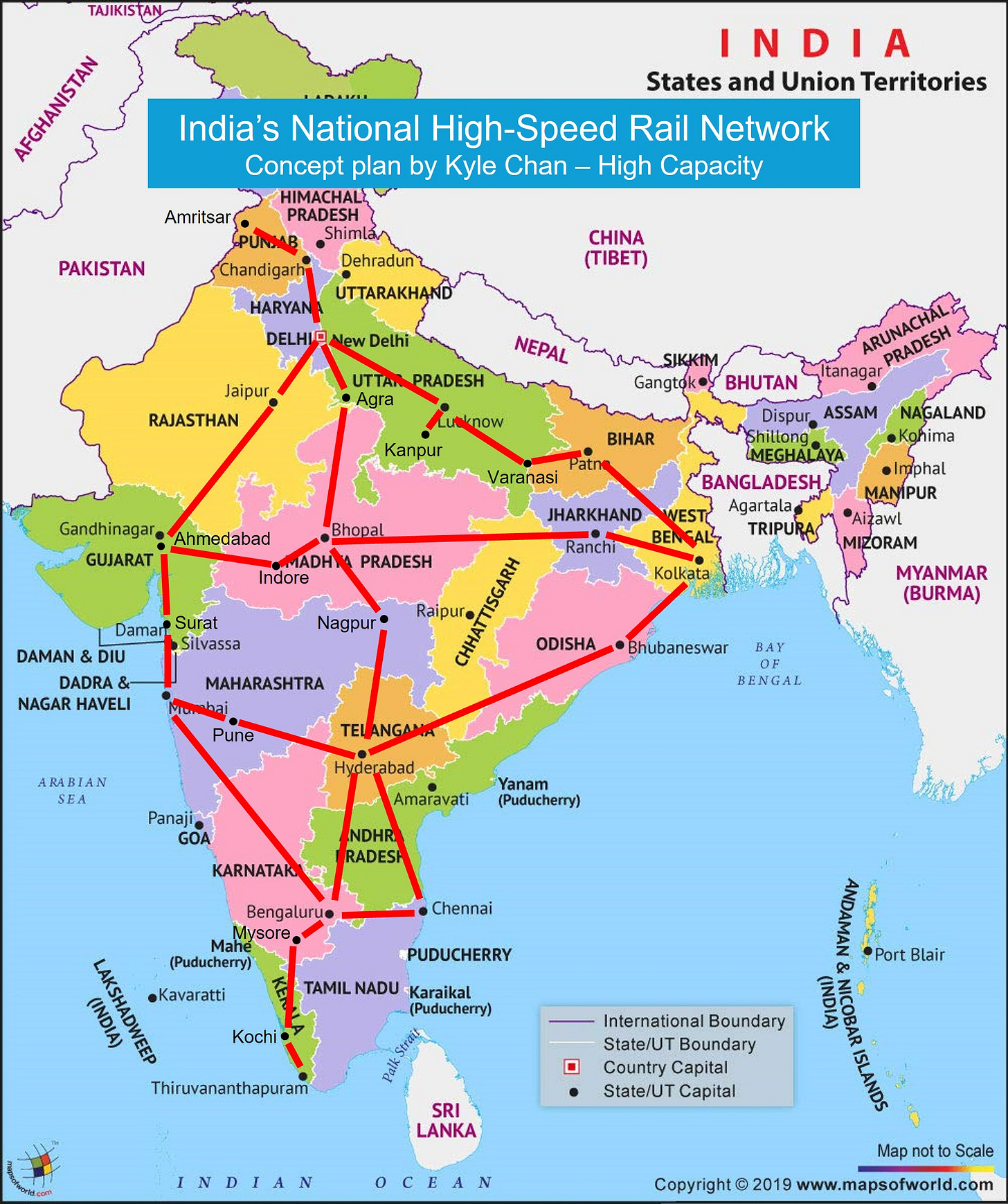

To give a rough sense of what a national HSR system might look like for India, I created the map above, which tries to connect most of the country’s largest cities in a parsimonious way. Using the “average journey speed” for the Beijing-Shanghai HSR (a normal trip takes 4.5 hours to travel 1,300 km with stops = 290 km/h), we can get some rough estimates for HSR trip durations in India:

Delhi-Mumbai: 4.5 hours (versus 16 hours currently)

Bangalore-Hyderabad: 2 hours

Delhi-Calcutta: 5.5 hours

Mumbai-Bangalore: 4 hours

Here are the top reasons why India in particular should really have a national HSR system.

India has a huge aviation industry. India has the third-largest aviation market in the world by passenger volume with over 200 million domestic passengers per year in 2019-20 and likely to reach 500 million passengers per year by 2030. This means there’s already huge demand for fast, long-distance travel in India—and many people willing to pay for it. Moreover, because of its size, India’s aviation is one of the highest-emitting aviation industries in the world. For both travel convenience and environmental reasons, it would be much better if many short-haul flights were replaced with bullet trains.

In China, HSR has already replaced a significant amount of air travel for distances of 1,000 km or less. A number of short-haul flights were cancelled after an HSR line was built, including Chengdu-Chongqing, Zhengzhou-Xi’an, and Wuhan-Guangzhou. Even for medium-range trips, travelers often prefer taking HSR over flying. For example, for the 600-km trip from Shanghai to Wenzhou, taking a 3.5-hour bullet train ride can be more convenient than a shorter, similarly priced 1.5-hour flight because you can avoid airport hassle, flight delays, and crammed airline seats.

India’s existing railways are congested. In a way, it’s a good problem to have. Decades of rapid economic growth and growing demand for mobility have outpaced India’s ability to build and expand its heavily used railway system, which is often called the “lifeline of a nation.” Track congestion is responsible for slow speeds and frequent delays (which I’m intimately familiar with from my many train journeys across the country). India’s current freight rail speeds average under 24 km/h. The problem is especially acute at regional hubs where freight and passenger trains converge onto track bottlenecks. Overcrowding is also a major safety issue.

One of the more counterintuitive things about HSR is that it not only makes passenger travel faster, but it can also make freight transportation faster by expanding rail capacity overall. A primary motivation for China’s HSR program was to free up conventional track for freight. One study found that China’s HSR system reduced the number of trucks on China’s highways by 15% by freeing up freight rail capacity, which turned out to be a key channel for reducing carbon emissions (as I discussed in previous piece).

Climate change and air pollution. India is the third largest carbon emitter behind China and the US (although India’s per capita emissions are far lower). Road transport makes up 12% of India’s carbon emissions. In 2019-2021, less than 8% of Indian households owned a car, which means future emissions from the purchase of additional gas-powered cars could be significant (although the rise of electric two- and three-wheelers could offset some of this). As mentioned earlier, India’s huge, growing aviation industry is another major source of emissions. India also has some of the highest air pollution levels in the world, which reduces India’s average life expectancy by 5.3 years (I often used air purifiers and N95 masks when living in Delhi as well as Beijing).

A national high-speed rail network can help with both carbon emissions and air pollution. One major study found that China’s HSR system reduced carbon emissions by over 11 million tons per year. These emissions savings will likely grow as China, like India, shifts away from its heavy reliance on coal for electricity. The Indian Railways has actually been making a strong push into clean energy, such as installing over 200 MW of rooftop solar on train stations, and Railway Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw has set a goal of reaching net-zero carbon emissions by 2030.

HSR can even support other carbon reduction efforts indirectly, such as the shift to electric vehicles. In India, “range anxiety” is a major barrier to EV adoption, as it is in other countries like the US. But in China, drivers are fine with shorter EV battery range because longer journeys can be done by HSR. This in turn helps lower the price of EVs in China and lowers barriers to EV adoption. See, for example, the chart below from John Paul Helveston showing EVs in China clustering in the lower-range, lower-price region (left chart) versus EVs in the US clustering in the higher-range, higher-price region (right chart).

But can India build a national high-speed rail network?

Absolutely. India has had major successes in building large-scale rail infrastructure.

The Delhi Metro is one example. Started in 1998, the Delhi Metro today carries an average of over 5 million passengers per day over nearly 400 km of track to 288 stations. The dizzying speed at which the Delhi Metro has been expanding rivals that of Chinese subway systems. Now multiple cities in India have similar metros in operation or underway, including Bangalore, Chennai, Hyderabad, and Mumbai.

Moreover, the development of metros in many Indian cities is actually complementary to a national high-speed rail system. As in the US, long-distance trips in India are sometimes made by car because a vehicle is needed at the destination. By having more metros—and more extensive metros—Indian travelers can get around exclusively by HSR and metro (and the occasional Ola or auto rickshaw), ditching their cars altogether as is common in China.

India’s Dedicated Freight Corridor (DFC) is another example. This project is a massive nation-spanning pair of freight rail lines stretching over 2,800 km that connects Delhi and other major cities with ports in Mumbai and Calcutta. The eastern half of the project is already operational and the western half is nearing completion. (I interviewed several of the project’s top leaders and will write a piece on the DFC later.) In addition to its metros and the DFC project, India has made huge strides in electrifying its rail network (it’s on track to reach 100% electrification in the next year or two) as well as adding extra capacity along existing lines through additional track (known as “line doubling”).

India is already building its first bullet train line. The $17 billion project, which is receiving a large amount of financial and technical support from Japan (specifically, JICA, which was also crucial for the Delhi Metro), is expected to transport passengers the 508-km distance between Mumbai and Ahmedabad in under 3 hours with a top speed of 320 km/h. The project began in 2017 and was originally supposed to start running by 2023 but faced a number of delays, primarily due to land issues and later COVID. But by January 2024, all land acquisition had been completed, and the first 50-km stretch is now scheduled to open by 2026. The very name of the government agency in charge of this project shows India’s greater ambitions for HSR: the National High-Speed Rail Corporation Limited (NHSRCL) formed in 2016. Both the BJP and Congress Party in India have made proposals for a larger HSR network in the past, including a “diamond quadrilateral” of bullet trains connecting India’s four largest cities.

Economic and social spillovers of HSR

A common mistake when thinking about major infrastructure projects like high-speed rail is to focus too narrowly on direct financial returns (“is it profitable or financially self-sustaining?”). For years, the Indian Railways paid an annual “railway dividend” to the central government, which was finally stopped in 2016-17. Railways are not a financial asset—they’re an economic and social asset to the nation. I would even go so far as to argue that railway networks and other high-impact infrastructure should be loss-making: government resources spent on operating and upgrading India’s railways are an investment in the nation’s broader economic development.

A number of studies have found evidence of these broader economic and social returns (i.e., “spillovers” in the world of economics) for both conventional railways and HSR. One study found that India’s railways during the British colonial period had significant positive spillover effects, including lowering trade costs, increasing trade, and raising incomes. Another study found that China’s HSR helped facilitate market integration and “stimulate the development of second- and third-tier cities.” Other studies have found innovation and knowledge spillovers from the greater in-person connections enabled by HSR.

It’s very difficult to capture the full economic and social benefits of not just a single HSR but a whole HSR network. HSR doesn’t just benefit the individual cities or regions that it runs through but boosts the entire national economy, connecting businesspeople, investors, researchers, and workers together across the country.

Regional HSR clusters

One of the greatest advantages of HSR is connecting clusters of nearby cities and their surrounding areas. China has been working to form several “megalopolises,” centered around major cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. The most prominent of these is China’s Greater Bay Area (GBA) which integrates several of the country’s most advanced high-tech, manufacturing, and financial centers including Shenzhen, Guangzhou, and Hong Kong into one megaregion with 71 million people and 11% of China’s GDP (see bottom of the map below). At the heart of this is a set of HSR lines that form the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express Rail Link (XRL) and create a “one-hour living circle” where people can essentially commute between these cities.

India could begin its national HSR rollout by creating regional HSR clusters. Here are some examples:

South India Tech Cluster: Bangalore-Hyderabad-Chennai

Industry & Finance Cluster: Mumbai-Surat-Ahmedabad-Pune

Capital Tech Cluster: Delhi-Chandigarh-Jaipur-Kanpur-Lucknow

The benefit of prioritizing these regional HSR clusters over longer HSR lines, at least in the early phase, would be to take advantage of existing regional connections in the most productive parts of the country and boost them further. In other words, because these areas are already regionally integrated and the most economically developed parts of the country, they’re likely to yield the greatest near-term nation-level economic return per km of HSR line built. (Arpit Gupta has also advocated for rapid regional rail, which could further enhance regional HSR clusters.)

The need for speed

Critics of HSR in India often point to the high costs and argue that the money would be better spent on improving India’s existing railways rather than on “luxury” bullet trains for the wealthy. People might be surprised to hear that there’s long been a similar debate over HSR in China. I spoke with Zhao Jian at Beijing Jiaotong University who cites enormous debt levels and continues to be an outspoken critic of more investment in China’s HSR.

But India is no longer a “low-income” country and has a large, rapidly growing middle class willing to pay for faster, long-distance travel (as evidenced by my earlier discussion of India’s aviation industry). When Japan launched its first Shinkansen bullet train in 1964, its GDP per capita was only $8,900, adjusted for inflation, and China’s was $4,700 in 2008 with the launch of its first bullet train. India’s GDP per capita is around $2,400 today (non-PPP), which is lower but still significant.

Bullet trains are also not just for the wealthy, although their customer base will obviously tend to skew towards the middle and upper class. In China, many low-wage migrant workers prefer to take high-speed trains over cheaper, slower buses or conventional trains that might cost them a full day or two of lost work. Here, pricing will be key to balance between recovering costs through fares while making HSR affordable to people across different income levels.

Construction costs in some areas can come down over time. China’s HSR program leveraged the scale of a national rollout to standardize technology and construction methods, spread out the cost of equipment and other capital investments, and bargain hard with foreign suppliers (as I previously wrote about). China also made heavy use of elevated track and tunnels, like Japan did, which can increase direct construction costs but reduce the need for expensive and disruptive land acquisition. Perhaps most importantly, you learn by doing. One Chinese railway official said to me that by doing many HSR projects, even relatively young project managers in China have had more experience building HSR than many people outside of China have in their entire careers.

Ultimately, speed matters. Having a slightly faster train service won’t be enough to win over people traveling by air. Bullet trains offer something qualitatively different from any other form of transportation and have the potential to transform India like its conventional railways did in the past. A country as large and rapidly developing as India needs to bet big on its future.

I heavily disagree.

But I'm going to start with where I agree. India should invest more in freight corridors to make its manufacturing sector more competitive. India currently taxes freight rail to subsidise passenger rail which is fucking stupid. If it hadn't done that India would have been able to build a lot more rail without handouts from the taxpayer.

India should also invest more in inter-city public transport. But many of the metro lines in India (including the ones in Delhi) aren't raising enough revenues. They should tap into other sources of revenues such as selling ads and renting out land around the stations. They should also invest more in feeder buses to increase ridership of metros and also create an integrated transport system. Even if the government subsidies the metro system it should do it using local property or land taxes instead of income taxes. Government expenditure in India is too centralised to begin.

I don't think a nation wide hsr network makes any sense. Some might. They should go through a process of calculating the economic rate of return. Otherwise they'll be a bunch of white elephant projects. I would like to remind people that the Japanese Shinkansen was a massive loss making system before it was privatised in the 80s.

I also don't think the emissions of the aviation sector is that big of a deal. The entire aviation sector is responsible for 2-3% of all emissions. From an emissions perspective metros and buses will give you a greater bang for your buck. By the time India will be done building HSR in 15 years, most short haul aviation will be electrified anyways. Long haul aviation won't be electrified within my lifetime though.

Before you get too enthusiastic about the future of HSR I would recommend reading about the first railway mania in Britain and USA. There is a bigger danger of this happening when public money is involved and you're making the case that they should be loss making.

India should look to what Europe is trying. The EU is starting to partially privatise its passenger railway system. I'm not too aware of the details. But given India's poor record of service delivery it should look towards getting more private sector participation.

Very good article Kyle. Three fundamental problem in India.

1. Indian politicians see national transportation & utility systems more like a private business profit making enterprise. Indian politicians have conservative & austerity mindset about public investment. Indian politicians have very narrow vision about economic and industrial policy making.

In recent times, more focus is on private investment & profit motive of systems. Private enterprises are asked to undertake giant investments which are not directly very profitable (although in long term they are highly valuable). In India people have very low purchasing power that's why for-profit private business models have failed. Delhi Metro is centrally funded and operated pretty much on no-profit basis. That's why it's successful. And with govt as main driver of investment, the growth of Delhi metro is remarkable.

But when metro projects are implemented by private corporations, the investment is very shaky. For example, the Mumbai metro project has expanded at snail's pace & long delays and commutation costs for riders is also very high. This type of model hasn't been successful. In recent past, Delhi metro also tried these kind of PPP models by privatizing a section of Delhi metro (Airport line) which ended in disaster.

https://www.hindustantimes.com/delhi/metro-chief-gives-the-thumbs-down-to-airport-metro-says-no-ppp-in-future/story-E5jphl8PZVoEqYkhjSgjIO.html

So problem is the mindset of politicians who do not wanna make investment in Indian economy and wish private sector substitute the role of public investment.

2. The funding part & lack of technical capability. Much of the earlier phases of Delhi metro & in fact many other infrastructure projects have been built with assistance of foreign firms and govts who have technical capacity. In fact, projects like Delhi metro was a good opportunity for Indian companies (that made joint ventures with foreign firms) to learn underground tunneling & construction of metro projects. Later, Indian firms became self sufficient in such construction skills.

For HSR construction, India i think is relying on Japanese technical assistance. Here the India has shrunk its opportunities. First, by austerity mindset and second by limiting foreign partnerships. India doesn't wanna invite Chinese firms for the project which i believe could be cheaper. The western firms for HSR construction are costly i believe.

3. There is a problem with India's eminent domain. Due to rural populist mindset of govt, they shell out heavily for acquiring land for projects. And if farmers think they're not getting adequate compensation, they go on agitations which politically destabilizes the govt. This is another sort of compulsion for govt.

To give you a small example. Metro project very near to my home was delayed for several years because political problems with land acquisition & legal hurdles.

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/missing-link-bridged-delhi-metros-pink-line-becomes-networks-longest-corridor/articleshow/85094859.cms

India really needs is go-big strategy for 21st century. Directly fund HSR project, tie up multiple joint ventures with other foreign firms for technical needs. This will make Indian firms self sufficient by next decade to work on their own.