Why Chinese EVs will not take over the world

Other automakers can leverage the same Chinese supply chain as well as manufacturing innovations like gigacasting. Plus, image and brand matter as much as price and performance. Look at Japanese cars.

Fanning the flames

Many countries are worried that Chinese electric vehicles will dominate the global auto market the way that China did with solar manufacturing where it has over 80% of global capacity. The US is discussing a ban on Chinese EVs on national security grounds while the EU is preparing tariffs that might be applied retroactively. Elon Musk claimed that "if there are no trade barriers established, they will pretty much demolish most other car companies in the world.” Trump warned of a “bloodbath” for the US auto industry. All the while, Chinese state media aren’t calming any nerves by boasting that “China dominates global new energy car sales.”

But I argue that fears of Chinese global domination in EVs are overblown. I’m not saying that Chinese EVs won’t sell very well and end up taking the top spots in global vehicle sales, which is more than likely. Instead, I’m pushing back against the hysteria over Chinese EVs wiping out existing automakers and taking away millions of jobs in a “China Shock 2.0” scenario. Ultimately, China’s success with cars will probably look more like Japan’s. Here’s why:

Everyone can leverage Chinese auto supply chains

While everyone is panicking over the surge in Chinese EVs, China has been quietly expanding across the auto parts and manufacturing supply chain. In a classic case study of Chinese industrial policy, China has been steadily building up its auto parts industry through subsidies, preferential treatment of Chinese suppliers, and joint ventures with foreign manufacturers. Today, China is the world’s second largest exporter of auto parts, reaching $53 billion in 2023.

You might think China’s growing dominance in the auto supply chain would give its EV makers an insurmountable edge. But remember that Chinese producers of auto parts and manufacturing equipment are very eager to sell to non-Chinese carmakers. Western and Japanese automakers can take advantage of the same Chinese auto supply chain as Chinese EV makers.

In many ways, they already have. China is already the second largest source of imported auto parts for the US. Chinese auto parts manufacturers are currently rushing to build factories in Mexico to supply non-Chinese carmakers, like Tesla which is currently building a “gigafactory” in Mexico. Chinese companies already export over $1 billion in auto parts from Mexico to the US, including “heating and cooling systems, shock-absorption products, metal components and other parts.” This is driven in part by the broader “China+1” trend where Western and Japanese automakers are pressuring Chinese parts manufacturers to move production to places like Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, and Mexico.

Tesla, China, and the “Giga Press”

The case of “gigacasting” shows how Western and Japanese automakers can take advantage of the same manufacturing equipment and techniques used by Chinese EV makers.

When Tesla entered China to set up Gigafactory Shanghai, it worked with a Chinese-owned equipment manufacturer to create the world’s largest casting machine, which Tesla calls the “Giga Press.” These massive machines, which are the size of a small house and can exert thousands of tons of pressure, allow Tesla to make an auto component as a single, large continuous piece instead of dozens of smaller pieces welded together. Idra Group, an Italian casting machine maker, and its Chinese owner LK Group worked “worked side by side with Tesla for over a year to make the machine,” according to LK Group’s founder.

Chinese EV makers have already seized on this new car manufacturing process called “gigacasting.” Xiaomi touts its “hypercasting” machines as a core technology behind its new flagship SU7 EVs. Its casting machines are rumored to be made by Hai Tian Die Casting (海天金属) based in Zhejiang. Several other Chinese EV makers such as BYD, Xpeng, NIO, and Geely are using or plan to use similar gigacasting machines made by Idra, LK Group, or Hai Tian. The use of gigacasting by Chinese EV firms contributes to their ability to churn out cars quickly and cheaply.

But gigacasting is also becoming popular with Western and Japanese automakers. Ford and Hyundai have already bought gigapresses from Idra. Volvo recently signed a deal to buy two 9,000-ton gigapresses from Idra. GM recently acquired a company that originally helped Tesla make its gigapresses. Other non-Chinese automakers that are also talking about gigacasting include Toyota, Honda, Subaru, and Volkswagen. Japanese and Swiss parts and equipment makers like Ryobi, Aisin, and Bühler are also jumping on the gigacasting bandwagon. The gigacasting trend is an example of how other carmakers aren’t just standing still but building on some of the same manufacturing breakthroughs used by Chinese EV companies.

Battery partnerships

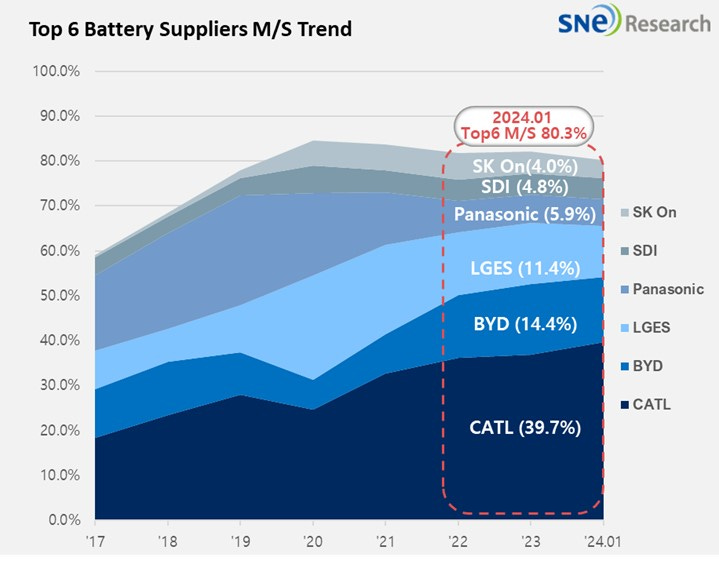

That’s great—but what about batteries? Batteries are the most valuable and technologically sophisticated component in EVs, making up around 40% of their total cost. And their production is dominated by Chinese firms like CATL (38% global market share) and BYD (13%). But non-Chinese EV makers can partner with Chinese battery makers to use their batteries or license their technology.

CATL, for one, is eager to partner with non-Chinese EV makers, like Ford and Tesla. In 2023, CATL announced a licensing agreement with Ford to build a $3.5 billion EV battery plant in Michigan using CATL’s technology. While Ford has cut back its plans in the face of opposition from US lawmakers, it’s still planning to build a 20 gigawatt-hour battery plant using CATL technology by 2026. Until then, Ford is using imported CATL batteries for vehicles like the Mustang Mach-E.

More recently, CATL and Tesla announced a partnership to produce fast-charging batteries and build a new battery plant in Nevada with CATL equipment. CATL is already a major supplier to Tesla, particularly for its made-in-China models. It also supplies EV batteries to other non-Chinese automakers, such as BMW and Mercedes. CATL is banking on these types of partnerships through its “licensing, royalty, and services” (LRS) model to get around efforts to block imported Chinese EV batteries.

BYD, the other Chinese EV battery giant, is following a similar licensing model. BYD, which also makes its own EVs (with 75% of its parts produced in-house), has licensing deals with foreign manufacturers for its battery technology. Tesla uses BYD battery cells, including for its Model Y made at Gigafactory Berlin. Ford and GM use BYD batteries through their US supplier BorgWarner, which has a licensing deal with BYD that includes intellectual property for battery design and the manufacturing process. Kia’s newest electric SUV will feature BYD batteries.

Non-Chinese automakers can also learn from Chinese manufacturers. Battery and related technology partnerships with Chinese firms can help other countries improve their own automakers. CATL is working with foreign automakers to bring their staff to China to receive training from CATL engineers. BYD is jointly producing EVs with Toyota. Toyota’s head of EVs spoke about his first visit to a Chinese EV factory:

“Laying eyes on equipment that I had never seen in Japan and their state-of-the-art manufacturing, I was struck by a sense of crisis—We’re in trouble! At the same time, I began to think that I would like to spend the rest of my career in China.”

Countries like the US, Japan, and India should use BYD and CATL the same way that China itself used Tesla to turbocharge its own EV industry. The irony is that not long ago, it was Chinese carmakers who were partnering with foreign carmakers to get their technology—and now in the age of EVs the tables have turned.

Strong brand and country loyalty

Another major reason why Chinese EVs won’t take over the world has nothing to do with gigapresses or supply chains. Buying a car is not just about hard specs or performance for price—it’s about an image. Look at American pickup trucks, which are the top-selling vehicles in the US across all categories. People are drawn to their image of American ruggedness in a way that defies mere pragmatism (as I often try to explain to European friends).

The Ford F-150 in particular is an American cultural icon that no other truck or car can really eclipse. The Ford F-series is the bestselling vehicle in 22 out of 50 US states and has been the bestselling US vehicle for the past 42 years in a row. Even though Toyota and Nissan offer popular, made-in-America competitors like the Tacoma and the Frontier, the top spots are still dominated by American auto brands. The obsession over Tesla’s Cybertruck is further proof of the intangible—and irrational—aesthetic appeal of these kinds of distinctly American vehicles.

Look at Japanese cars

I’ll end by looking at the best example for what might happen with Chinese EVs: the rise of Japanese automakers.

There was a time when Americans were terrified of Japanese automakers flooding the US market and running Detroit out of business. These fears surged after the 1979 oil shock when cheaper, more fuel-efficient Japanese cars looked poised to crush their American competitors. But today, Japanese cars only have about a third of the US market. So what happened?

In the 1970s, the US was growing increasingly concerned about its trade deficit with Japan, which had become a hot political issue (sound familiar?). In 1981, the US struck a deal where Japan agreed to “voluntary export restraints,” limiting Japanese car exports to the US to 1.68 million per year. In addition, the US pressured Japanese automakers to move production to the US. Since then, Toyota and Honda have each made over 30 million vehicles in the US. Meanwhile, US automakers had time to catch up and even learn production techniques from Japanese carmakers, exemplified by GM’s joint venture with Toyota: the legendary NUMMI plant in Fremont, California.

By the time export restraints ended in 1994, Japanese carmakers had moved a large share of their production to the US, and American automakers were ready to compete again. Today, Japanese cars sell well in the US and around the world. But they never did wipe out American and German automakers as was feared. Given the reasons I’ve listed, I expect Chinese EV makers in the future to look more like Japanese cars today: very successful, but not all-conquering.

Of course, there are some important caveats to this comparison. As tense as the relationship got, Japan was a close US ally and fellow democracy, which permits vastly more room for negotiation and compromise. China, as a geopolitical rival, might not even be allowed to set up auto plants in the US the way that Japanese automakers did (although Trump seemed to be open to the idea, saying “if they want to build a plant in Michigan, in Ohio, in South Carolina, they can, using American workers, they can”).

The US also did take political and policy action with Japan to alter what had seemed like a perilous trajectory for US automakers. I realize this argument may sound a bit circular, but my final point is that the rest of the world won’t just stand idly by and can take policy action to limit sales of Chinese EVs to their markets. Power is ultimately in their hands as the potential customers, so China would do well to tread carefully and avoid triggering further backlash (as I’ve written about here).

More on gigapresses:

Isn’t the Japanese case an example in support of import tariffs and restrictions then?

So the title of this piece is more an expression of confidence that these tariffs/restrictions will emerge and prevail?

I’m also unsure how the parts business can allay concerns substantially at the “whole cars” level - I suppose the argument is that Chinese government has an incentive to ensure there are buyers for sellers for car parts (and not just cars)? Perhaps it is only owing to subsidies, but if whole cars from china are vastly lower in price than local cars of similar quality, then the argument turns back to the Japanese question of whether import restrictions are necessary.

I have no doubt that the f150 is iconic, but this is a petrol car. The matter at hand is the future of electric cars, and Chinese technology appears ahead on the cost curve for the key inputs (and whole products) there. So it is unclear that iconic brands can survive in this new category.

Very good article. How much of the supply chain can be leveraged enough while keeping the cost advantage going do you think? The price delta for a BYD seems pretty high already, and that advantage did work for Japanese automakers Vs their competition, even though they had a bit of protectionist benefit from an (initially) closed market.