Why the U.S. CHIPS Act matters to the world

More semiconductor plants will help the US. But how will it help the rest of the world?

The US just announced a massive funding package for Intel to expand semiconductor manufacturing in the US, including $8.5 billion in grants and $11 billion in concessional loans. Major chip manufacturers have already announced or begun construction on over $200 billion worth of US manufacturing facilities in response to the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act. However, this latest announcement proves that the CHIPS Act is “real” and that the $39 billion in funding allocated for chip manufacturing will indeed be deployed at scale. This helps not just Intel’s plants but also all of the other chip-related projects waiting for CHIPS Act funding, most notably TSMC’s Arizona plant.

This benefits not just the US but also the rest of the world.

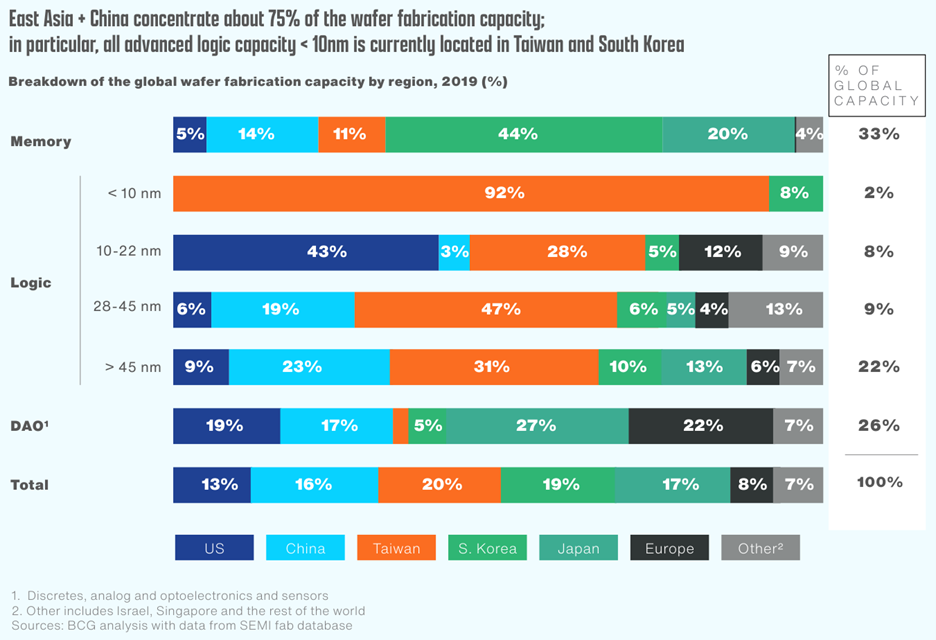

Semiconductor manufacturing, particularly at the high-end, is far too concentrated in a few firms and and a few countries. Over 70% of chips are manufactured in East Asia, and over 90% of advanced chips (less than 10 nm) are made in Taiwan.

TSMC alone controls almost 60% of the global semiconductor manufacturing market, and 15 of its 18 plants are located in Taiwan, including all of its most advanced chipmaking plants. If chips are the new oil, the semiconductor industry actually suffers from even greater concentration. For comparison, OPEC controls only 40% of global oil production, and Saudi Arabia only 12%.

This degree of concentration risk means that if anything goes wrong with Taiwan or TSMC, it could have devastating economic effects on the $6 trillion of global economic activity that rely on semiconductors as a direct input. While the risk of a Chinese military operation has received the most attention, there are plenty of other risks, such as natural disasters (Taiwan is prone to earthquakes, flooding, and droughts), constraints on Taiwan’s land and natural resources, and a limited talent pool of engineers and operators.

Global semiconductor manufacturing capacity is far too limited to meet the growing demands of AI. The pandemic chip shortage showed how an undersupply of semiconductors can hurt many sectors of the global economy, from smartphones and computers to auto manufacturing. While that chip shortage has now turned into supply glut, there are signs that we may already be entering another cycle of surging demand.

Add to this the massive wave of demand for GPUs and other AI chips already underway in the global race to build generative AI models, culminating most recently with OpenAI CEO Sam Altman’s call for $7 trillion to expand chip manufacturing. At the heart of this is the seemingly insatiable demand for Nvidia’s GPUs, which are primarily manufactured by TSMC. However, TSMC is already becoming a bottleneck for Nvidia, which may consider shifting some production to other chip foundries, such as Intel.

Enter, the CHIPS Act. Expanding semiconductor manufacturing, particularly at the high end, in the United States would help reduce concentration risk in Taiwan and expand global production capacity. This would help insulate the global economy from the kinds of chip production bottlenecks we experienced during the pandemic while fueling the AI ambitions of companies and governments around the world. Other countries are already playing their part, most notably Japan, which recently completed its first $8.6 billion TSMC plant and is already planning a second TSMC plant scheduled to open by 2027.

What about China?

China has been working hard to build up its own domestic chipmaking capacity, particularly in response to chip restrictions and other technology export controls from the US designed to limit China’s access to advanced semiconductors. An analysis by CSIS called this “a new U.S. policy of actively strangling large segments of the Chinese technology industry—strangling with an intent to kill.”

US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan laid out a more aggressive shift in US technology policy towards China in a 2022 speech:

On export controls, we have to revisit the longstanding premise of maintaining “relative” advantages over competitors in certain key technologies. We previously maintained a “sliding scale” approach that said we need to stay only a couple of generations ahead.

That is not the strategic environment we are in today.

Given the foundational nature of certain technologies, such as advanced logic and memory chips, we must maintain as large of a lead as possible.

In other words, whereas previously the US only wanted to maintain a relative lead over China in semiconductors, now the US is looking to actively widen the technology gap with China. The CHIPS Act serves this purpose by bringing high-end chip manufacturing to the US where it previously didn’t exist.

There is one possible but highly speculative way that China might benefit, or at least get some relief. If the US is indeed able to increase its own high-end semiconductor manufacturing capabilities, it may feel less need to put so much energy into keeping China’s chip industry down.

The US is expending diplomatic capital in pressuring allies—particularly the Netherlands, Japan, and South Korea—to restrict sales of semiconductor tools to China. However, this comes at a cost to these countries in terms of lost sales to China and potential economic retaliation from China. The Netherlands’ ASML has pushed back, arguing that export restrictions may backfire by spurring China to develop its own lithography equipment. Japan faced domestic pressure from Tokyo Electron, which is a major supplier to Chinese semiconductor firms.

If the US feels that it’s able to maintain or even grow its lead over China by increasing US chipmaking capacity, then it may be less inclined to strain relationships with allies through greater export controls. Of course, what really matters is China’s own progress on semiconductors. When Huawei surprised the world with a new cutting-edge smartphone chip made with SMIC, US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo vowed to take the “strongest possible” action in response. The US is now considering additional sanctions on Chinese chip-related firms that supported Huawei’s chip breakthrough.

I root for the underdog, against the global bully with the Tonya Harding syndrome.

Kyle, yours is a subtle but pro-US stance.