Huawei the Hydra

A closer look at the crown jewel of China's industrial policy through Eva Dou's new book House of Huawei

This piece is a discussion of Huawei’s role in China’s industrial policy, centered on Eva Dou’s incredible new book House of Huawei. A version of this piece has been published in Phenomenal World. Special thanks to Jack Gross, Emma Fajgenbaum, and the team at Phenomenal World.

China’s tech titans gathered for a high-profile meeting with President Xi Jinping on February 17 in a moment designed to showcase Beijing’s support for private-sector innovation. In attendance was a “who’s who” of China’s leading technology companies, including the founders of DeepSeek, BYD, Tencent, and Alibaba. As observers pored over the seating arrangement, looking to see who might be favored by China’s top leaders, few were surprised by the person who occupied the most prominent seat, in the center of the front row: Ren Zhengfei, the founder and CEO of Huawei.

No ordinary company

Huawei stands at the heart of China’s technological ambitions. Founded in 1987 as a small supplier of telephone switches, Huawei has transformed into a globe-spanning giant, making over $100 billion a year selling everything from 5G infrastructure and video conferencing equipment to smartphones and smart watches. Huawei is a central actor in China’s Digital Silk Road Initiative, which aims to develop digital infrastructure around the world using Chinese technology. A partial subsidiary is currently connecting three continents with undersea cables, and now Huawei is providing the semiconductor chips and digital systems that drive China’s booming artificial intelligence and electric vehicle industries.

House of Huawei, a new book by Washington Post technology reporter Eva Dou, offers a riveting account of Huawei’s rise and the enigmatic founder behind it all. Deeply researched and rich with detail, the book draws on a vast array of sources—from interviews with former Huawei executives and internal corporate documents to Ren Zhengfei’s own personal writings—to shed light on a company that has come to embody China’s emergence as a technological powerhouse.

The book is all the more impressive given the company’s notoriously secretive culture and the author’s limited official access to Huawei and its founder. What is Huawei trying to do exactly? Can the company be trusted? What does Huawei’s story reveal about China’s long-term ambitions? Through careful detective work, Eva Dou offers not a single definitive answer to these questions but enough facts and details for the reader to arrive at their own conclusion.

Huawei’s story is central to the broader history of China’s industrial policy, which can be viewed as a series of frantic races to patch up the country’s technological vulnerabilities and reduce its reliance on foreign powers. Wave after wave of Chinese industrial policy initiatives—from the 863 Science and Technology Program of the 1980s to Made in China 2025—have aimed to make China self-reliant for the so-called core technologies (核心技术) that underpin its economic development and national security.

Building a telecom army

In the 1980s, that core technology was telecommunications equipment. As China’s economy began to take off, Chinese political leaders saw their dependence on foreign telecommunications equipment as a critical threat to the country’s technological sovereignty. At the time, China relied completely on imported equipment from foreign companies, such as Ericsson, Nokia, and Siemens. In addition to costing a fortune in foreign currency reserves, relying on foreign equipment meant giving up control over a fundamental part of China’s modern infrastructure. Huawei’s founder Ren Zhengfei famously told Chinese President Jiang Zemin: “A country without its own program-controlled switches is like one without an army.”1

To acquire foreign technology and develop its own telecom industry, China used the promise of its vast and growing domestic market to actively bring in foreign equipment makers and have them form joint ventures with Chinese firms. The exchange of market access for foreign technology (市场换技术) began in China’s auto sector and would become a signature industrial policy strategy across many sectors for the subsequent decades. In 1984, Shanghai Bell was established as the first of these telecom equipment joint ventures, formed as a partnership with the Bell Telephone Manufacturing Company, a Belgium-based offshoot of Alexander Graham Bell’s original company. Other joint ventures with foreign companies soon followed, and by the 1990s China had successfully shifted from importing telecom equipment to producing most of it domestically through these joint ventures.2

Though its name is hardly known today, Shanghai Bell played a foundational role in China’s telecom development, not only bringing in core technology but perhaps even more importantly training a generation of Chinese scientists and engineers. A consortium of Chinese research groups, including an engineering institute under the People’s Liberation Army, carefully studied the Shanghai Bell’s technology and used it to develop China’s first domestically designed digital switches. A new state-owned company called Great Dragon was formed to commercialize these new Chinese switches. And it was Great Dragon, not Huawei, that was originally anointed China’s national champion for telecom equipment.

Fortunately for China’s telecom industry, Beijing didn’t put all its eggs in one basket. Great Dragon was one of four major Chinese equipment makers that also included Huawei, ZTE, and Datang. These four Chinese companies all benefited from the broader diffusion of technology through Shanghai Bell and raced to win market share across China as the country rapidly installed new telecom infrastructure. In an existential calamity for Great Dragon, its switches ran into software problems that basically knocked it out of the race.

Had Beijing simply given Great Dragon a monopoly over China’s telecom equipment, this would have been a disaster for the entire country. But China had deliberately created space for multiple strong competitors to emerge so that the industry overall would continue to make progress.3 Over time, China would use this strategy of “managed competition” in a range of industries, from the automotive sector to high-speed rail. Rather than creating a single state monopoly or simply leaving things to market forces, China would try to get the best of both worlds by honing a few key industry players and letting them compete in a supervised setting.

The rise of a national champion

How did Huawei end up becoming China’s national champion? Much of it was due to the hard-charging, military-style ethos cultivated at Huawei by founder Ren Zhengfei, a former engineer in the People’s Liberation Army. Ren fostered a fiercely competitive environment for his sales staff, known as “wolf culture.” He would organize “mass resignation” events where each sales manager had to write a sales report and a resignation letter, and Ren would only accept one—an approach Elon Musk would likely admire. Ren invested heavily in research and development, luring top scientists and engineers with generous pay and a chance to work on state-of-the-art technology. Huawei engineers were known for working long hours and famously bringing in mattresses to sleep in the office. Ren made nationalism a key motivating force for the company and appealed to national leaders like Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and now Xi Jinping.

Huawei also benefited from international cooperation. The company set up more than twenty research and development centers across the U.S. and Europe.4 It sponsored research collaborations with universities around the world. And it partnered with leading foreign companies, such as Nortel, Nokia, and Motorola. At the same time, Huawei was frequently accused of stealing intellectual property from competitors. One landmark case brought by Cisco claimed that Huawei’s software even had the same bugs as Cisco’s source code and that portions of Cisco’s technical manuals had been copied directly. Desperate for options during the lawsuit, Ren even considered selling Huawei to Motorola. Taken together, the factors that drove Huawei’s success—relentless ambition, global partnerships, and controversial tactics—were many of the same ones behind China’s technological and industrial ascent over the same period.

On top of the world

Huawei’s global expansion mirrored—and indeed spearheaded—China’s own emergence on the world stage. Huawei began by obtaining a foothold in countries that were viewed warily by the West, such as Iraq and Iran. From there, Huawei steadily expanded to other countries, beating out Western competitors on cost with support from Beijing. China Development Bank created a $10 billion credit line to finance Huawei equipment abroad, and Chinese leaders such as President Hu Jintao personally attended some of Huawei’s deal-signing ceremonies with foreign leaders.

Huawei’s international rise reached a tipping point in 2005 when the United Kingdom agreed to install its telecom equipment, which “broke open the dam into the West” and allowed Huawei to reach “not just individual countries but entire continents,” as Eva Dou described it.5 By 2015, Huawei supplied half of Europe’s 4G equipment. By 2020, it had become the world’s bestselling smartphone maker. Huawei and China had finally won the international trust and respect they had long sought.

But there were reasons for growing mistrust, too. American suspicions of Huawei began as far back as the early 2000s when the U.S. questioned whether Huawei’s infrastructure projects in Iraq had violated UN sanctions.6 In 2011, Huawei sold systems to Iran that allowed its police to track cell phone locations. In 2012, Huawei and ZTE executives were questioned before the U.S. House Intelligence Committee, which later concluded that both companies posed a risk to American national security. A 2017 report found that data from the African Union’s Chinese-built, Huawei-equipped headquarters had been secretly flowing back to China for years. In 2018, Australia became the first country to explicitly ban Huawei and ZTE from building its 5G infrastructure. Reports in 2020 and 2021 found that Huawei had developed sophisticated surveillance systems for use in Xinjiang and later other parts of China.

At a UK parliamentary hearing, Huawei’s head of cybersecurity said the company’s telecom equipment did indeed track cellphone location data because that was simply how modern cell technology worked. “Huawei’s equipment is no different from anyone else’s equipment,” he argued.7 The great irony was that the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) itself had hacked into Huawei’s servers in Shenzhen and sought to use Huawei equipment to spy on other countries, as revealed by the Edward Snowden leaks.

Huawei under fire

Then on May 15, 2019, Huawei received news that every prominent Chinese tech company has come to dread: it was placed on the U.S. Department of Commerce’s infamous “Entity List” by the first Trump administration. This blacklisting dealt a devastating blow to Huawei by cutting it off from the American chips and software that powered its smartphones, including Google’s Android operating system. Ren Zhengfei made the difficult decision to sell off Huawei’s popular Honor smartphone unit in 2020 for $15 billion. Huawei’s revenue the next year fell by 27 percent.

These were followed by escalating sanctions that ultimately blocked Huawei from using Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s leading chipmaker, to produce semiconductor chips. Huawei’s smartphone business went into a tailspin, and many wondered whether Huawei as a company could continue to survive. Throughout all this, Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s CFO and Ren Zhengfei’s daughter, was under house arrest in Canada as the U.S. pursued charges against her for allegedly violating sanctions on Iran. Public opinion in Canada was split over whether Meng Wanzhou should have been arrested, and the controversy only deepened when President Trump suggested Meng was a bargaining chip in negotiating a trade deal with China.

Under pressure on multiple fronts, Ren Zhengfei put Huawei into war mode. His firm had spent billions of dollars stockpiling enough semiconductor chips to last for two years; HiSilicon, Huawei’s chip design unit, had been working for years to develop “spare tires” in case Huawei lost access to foreign chips.8 And now Huawei threw the full weight of its formidable R&D capabilities into developing its own chips and operating system. What had previously been a backup plan transformed overnight into Huawei’s top priority. To inspire his staff, Ren circulated an image of a World War II-era Soviet bomber continuing to fly after suffering heavy damage.9

US-China tech war

It was not just an attack on Huawei but the beginning of a tech war waged against China by both the Trump and Biden administrations through escalating sanctions aimed at the heart of the modern economy: semiconductor chips. The U.S. cut China off not only from advanced semiconductor chips, like the most powerful versions of Nvidia’s GPUs, but also from the very tools China needed to make its own high-end chips, such as state-of-the-art lithography machines from the Netherlands’ ASML. The fight to restrict Chinese access to semiconductors took on an existential dimension in US politics. Just before the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan gave a speech arguing that the US “must maintain as large of a lead as possible.”

Now, after struggling for decades to catch up, China’s chip industry has been jolted into action by the threat of sanctions. Huawei has been tasked with leading a “Manhattan Project” to make China’s entire semiconductor supply chain self-sufficient. As an “industrial supply chain leading enterprise” (产业链龙头企业), Huawei has been deploying special task forces to help Chinese semiconductor companies across the supply chain solve production challenges. And the company has invested heavily in two massive R&D facilities in Shanghai and Shenzhen working around the clock to develop chipmaking equipment that can replace ASML’s cutting-edge EUV lithography machines now blocked by the Netherlands. Huawei’s existential imperative to harden itself against sanctions has aligned perfectly with that of China’s.

Huawei the Hydra

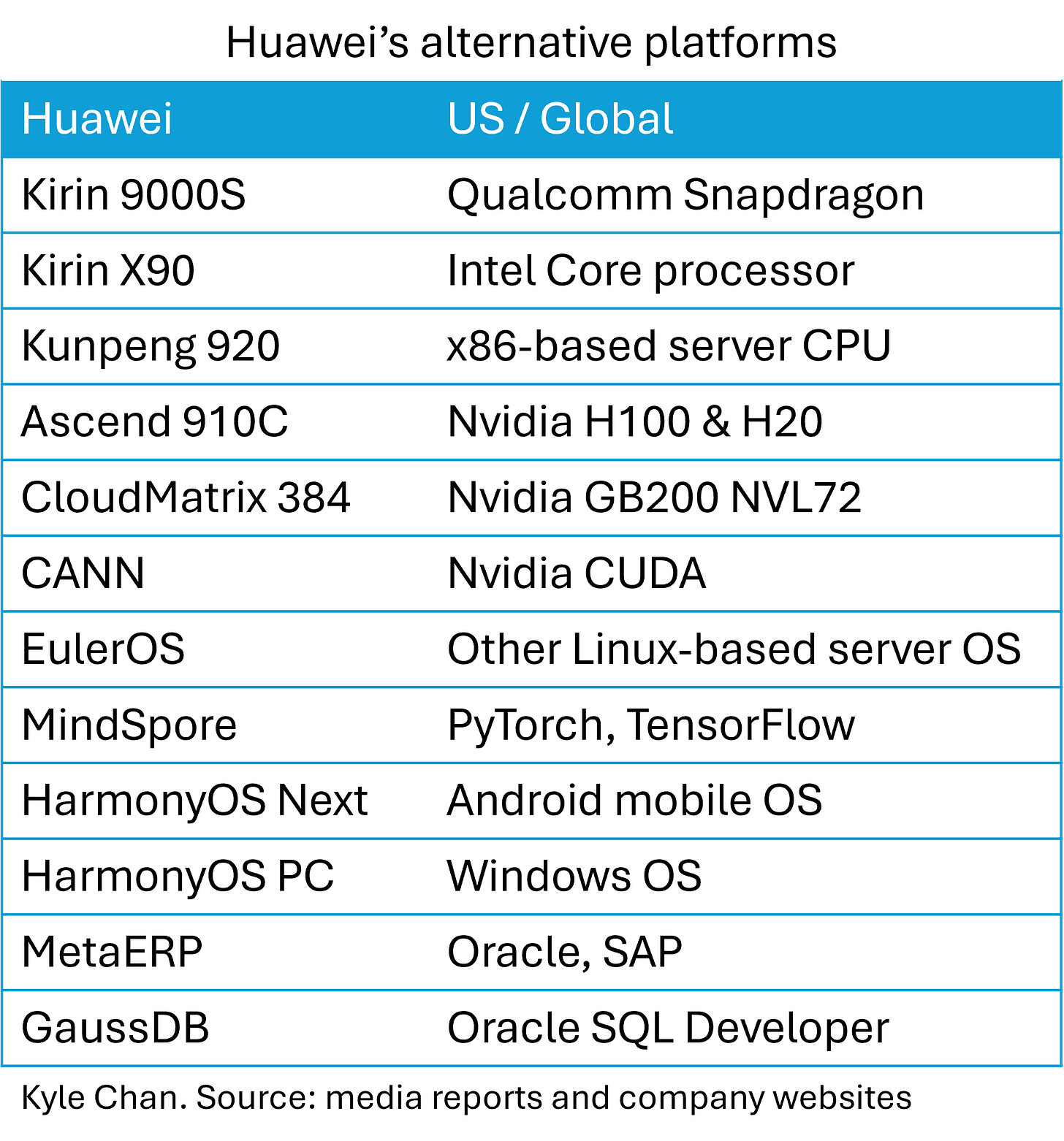

Less than five years later, Huawei shocked the world with a new product. In August 2023, Huawei launched a new 5G smartphone called the Mate 60 Pro that used Chinese advanced processor chips in defiance of U.S. efforts to hold back China’s chip industry. Then, in December 2024, Huawei launched a fully in-house version of its smartphone operating system called HarmonyOS Next. Huawei’s AI chips are now being used widely by Chinese AI companies, providing an alternative to export-controlled GPUs from Nvidia. As a result of Huawei’s progress, Ren Zhengfei recently told President Xi that concerns over China’s “lack of core and soul” (缺芯少魂)—meaning, lack of domestically-made semiconductors and operating systems—had eased.

Huawei’s unexpected advances combined with DeepSeek’s stunning breakthroughs in AI have raised questions about whether restricting China’s access to technology may have ultimately backfired. By forcing China to become self-reliant, the question is whether these policies had in fact accelerated China’s technological development rather than hindered it. China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi pushed back on U.S. sanctions in a recent speech: “Where there is a blockade, there are breakthroughs; where there is suppression, there is innovation” (哪里有封锁,哪里就有突围;哪里有打压,哪里就有创新). Huawei and its high-caliber army of engineers and scientists may have been a crucial variable that these policies had overlooked. Now, with Trump back in the White House and U.S.-China tensions heating up, China will need Huawei more than ever, its champion of national champions.

House of Huawei, p. 66.

Mu, Qing and Keun lee. 2005. “Knowledge Diffusion, Market Segmentation and Technological Catch-up: The Case of the Telecommunication Industry in China.” Research Policy, 34: 759-783.

Harwit, Eric. 2007. “Building China’s Telecommunications Network: Industrial Policy and the Role of Chinese State-Owned, Foreign and Private Domestic Enterprises.” The China Quarterly, 190: 311-332.

Pawlicki, Peter. 2017. “Challenger Multinationals in Telecommunications: Huawei and ZTE” in Jan Drahokouil (ed.) Chinese Investment in Europe: Corporate Strategies and Labour Relations. European Trade Union Institute. p.36.

House of Huawei, p. 160.

House of Huawei, p. 141.

House of Huawei, p. 208.

House of Huawei, p. 301.

Ibid.

I need to read this book! I'm starting to think differently about investing in China as I wrestle with my American arrogance.

"Huawei’s founder Ren Zhengfei famously told Chinese President Jiang Zemin: 'A country without its own program-controlled switches is like one without an army.'"

Mind-boggling that no influential American politician or businessperson realized this until far too late.