The China Shock revisited

The famous "China Shock" paper got blown out of proportion for reasons that are more sociological than economic.

The ”China Shock” paper (actually a set of papers)1 sent shockwaves through the US political world when it was first released by a team of high-profile economists in January 2016. It estimated the US lost nearly 1 million manufacturing jobs from 1999 to 2011 due to a surge in Chinese imports starting around the time of China’s accession to the WTO in 2001.

The paper seemed to provide support for a growing narrative that trade—and specifically trade with China—was to blame for the decline of American manufacturing jobs. While this is not what the paper actually argued, its more nuanced findings were lost in much of the political debate. In November of that year, Donald Trump won the US presidential election for the first time and the rest is history.

Many American manufacturing jobs have indeed been lost to China. And many American families and communities have been devastated by the losses of these jobs. But the paper’s impact went far beyond its intended scope and illustrates the dangers of how research can be oversimplified and misused in public debates.

Even if you accept the paper’s estimate of nearly 1 million US manufacturing jobs lost to Chinese imports, this needs to be seen in the context of a much bigger structural shift in the US economy that has been taking place since the end of World War II. For decades, the US has been moving away from manufacturing jobs and toward service sector jobs. While rising Chinese imports did contribute to the loss of some US manufacturing jobs, it was far from the main cause.

This first chart should already give you pause. It shows that manufacturing jobs as a share of all US jobs has been declining for decades, long before NAFTA came into effect on January 1, 1994 and China’s WTO accession on December 11, 2001.

This is because US service sector jobs have been booming for over half a century while US manufacturing jobs have been relatively stable by comparison, as this next chart shows. Since WWII, the US has added over 100 million service sector jobs. Think: healthcare workers, IT specialists, legal assistants, and TikTok influencers.

If you drill down in the next chart, you’ll see the absolute number of US manufacturing jobs has been declining since its 1979 peak of 19 million workers. From the peak in 1979 to the bottom in early 2010, the US lost over 8 million manufacturing jobs.

You can see two large drops in manufacturing jobs (although they look exaggerated in this chart because the y-axis starts at 7,500 rather than zero). One is around 2001, which is when China joined the WTO. The other is around the 2008-09 Great Recession. If you add these together, the US lost 5.8 million manufacturing jobs from 1999 to 2011.

You might be tempted to think all of these jobs got outsourced to China. But that would be a mistake. Other factors contributed to the decline in US manufacturing jobs during the same time period:

Economic downturns, one of which was the largest since the Great Depression

Rising productivity, including rising automation

Declining relative competitiveness of US manufacturing exports

Declining union membership and bargaining power

Rising imports from other countries besides China

Of these factors, the impact of automation on manufacturing jobs has been particularly well documented by a slew of high-quality studies. This helps to explain why US manufacturing output has remained fairly constant even as manufacturing jobs declined.

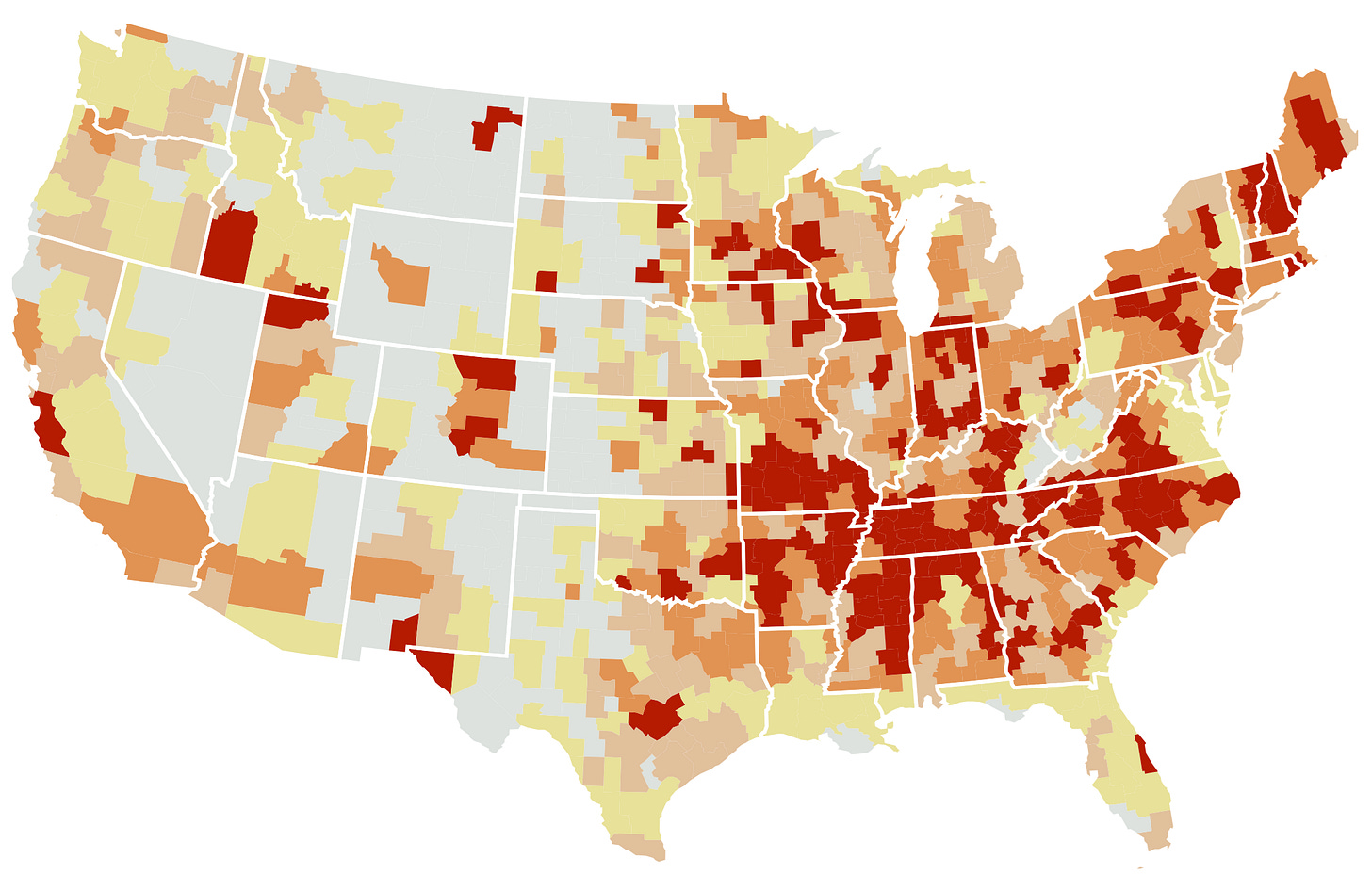

The China Shock paper does try to carefully identify what share of lost manufacturing jobs were specifically caused by rising Chinese imports rather than other factors. The paper estimates 560,000 manufacturing jobs were lost directly due to rising Chinese imports from 1999 to 2011 while an additional 425,000 manufacturing jobs were lost indirectly. If you add these up, you get a total of 985,000—nearly 1 million—manufacturing jobs lost.

While 1 million still sounds like a big number, it’s not quite as massive when you put it into context. We’re talking about 1 million jobs lost over more than a decade. From year to year, the number of US manufacturing jobs can fluctuate by as much as 1 or 2 million. Also, during this period, the total size of the US workforce was around 140 million, so we’re talking about a less than 1% impact on overall jobs at a time when overall employment is growing by millions. Even if you include the additional 1 million service jobs that the paper found were indirectly lost to China, this is still less than 1.5% of total jobs during this period.

Here’s another way to put it in context. Remember that from the peak in 1979, the US lost about 8 million manufacturing jobs. So using the estimates from the China Shock paper, rising Chinese imports were only responsible for 7% of the 8 million manufacturing jobs lost from the peak if you’re looking at direct losses and 12% if you’re looking at both direct and indirect losses. It’s not nothing. But it’s certainly much different than the narrative that China basically destroyed American manufacturing.

Finally, it’s just one paper. (Technically it’s a set of papers, as I mentioned in the footnote, but they build on each other using the same techniques and were written by roughly the same set of authors.) Even though the China Shock paper does a careful job of teasing out causation by using a well-known econometric technique called the Bartik shift-share approach, it is far from definitive and doesn’t offer the full picture.

A different set of papers shows that while some US manufacturing jobs were lost to China, many more jobs were created in the US due to greater US exports during the same time period. Another paper shows that many manufacturing workers impacted by Chinese imports actually switched to service jobs—often as part of a broader pivot from manufacturing to services by their employers. Other papers have found smaller job losses using a different approach or even a net gain in local jobs due to China trade exposure.

Rarely, if ever, does a single research study provide the definitive answer to a question. This is especially true in the social sciences where you often can’t run controlled experiments. Scholars and experts are therefore cautious when extrapolating from findings in a single study, looking instead to a consensus that builds across multiple studies. But a single paper can take on a life of its own, being seized upon by people with neither the interest nor the expertise to understand the nuances of its claims.

Sociology of the China Shock paper

There are several sociological reasons why the China Shock paper had such a huge impact. The biggest reason is that it fit with a popular narrative that was gaining traction at the time: namely that trade caused the death of American manufacturing, particularly trade with China. Another factor is the prestige of the authors, which included David Autor, a renowned economist at MIT. Even details of the paper mattered, like the fact that it offered a clear numerical estimate—nearly 1 million jobs—that people could point to and remember.

There’s another obvious but crucial factor: an eye-catching title makes a world of difference. The very word “shock” rather than “impact” or “effect” was, well, shocking. To this day, we still talk about the “China shock” or now the “second China shock.” In economics, a “shock” is actually a technical term that doesn’t mean “shocking” in magnitude but refers to a factor that was unforeseen and “exogenous” or outside the normal model.

The China Shock paper helped to fuel an overcorrection in American views on trade. For years, the prevailing orthodoxy was that free trade was an unadulterated good that made everyone better off. Many careful thinkers did see the more subtle point the China Shock paper was making: trade didn’t always make everyone better off, and the downsides could be concentrated in certain groups or communities. This was an important and useful correction to the old consensus. But too many people went too far to the other extreme, only focusing on the downsides of trade.

Perhaps the bigger shock now is that a simple idea blown far out of proportion can rock the entire global economy.

Further reading:

Scott Kennedy and Ilaria Mazzocco. 2022. The China Shock: Reevaluating the Debate. CSIS.

Scott Lincicome and Arjun Anand. 2023. The “China Shock” Demystified: Its Origins, Effects, and Lessons for Today. Cato Institute.

YiLi Chien and Paul Morris. 2017. Is U.S. Manufacturing Really Declining? St. Louis Fed.

Katelynn Harris. 2020. Forty years of falling manufacturing employment. US Bureau of Labor Statistics.

It’s actually a series of papers. The 2016 working paper “The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade” is actually a review article that was later published in the Annual Review of Economics. The review paper cites another paper first made available in 2014 titled “Import Competition and the Great U.S. Employment Sag of the 2000s.” And that paper builds on another high-impact paper published in 2013 titled “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States.” All of these papers are part of a broader research project on the impact of China trade on US labor markets carried out by a set of economists. For the sake of brevity, I refer to this whole set of interconnected papers as the “China Shock paper.”

Great work as always Kyle!

It would be fun to see a like time sequence graph of the fall of agricultural jobs. We grow more food with less people. I never hear anyone complain about that.