Will Biden's Chinese EV tariffs work?

Will tariffs give the US auto industry time to catch up to Chinese EVs? Or will the US become the Galapagos of the car world?

(This piece builds on an earlier piece: Why Chinese EVs won’t take over the world.)

Biden is trying to thread the needle on three major priorities at the same time: manufacturing jobs, decarbonization, and China. Some policies are targeted at one thing, like semiconductor export controls to China. Some try to do two things at once, like the IRA and clean energy jobs. But doing all three at once is a tough act to pull off. This time, it was decarbonization that was sacrificed for the goals of creating (or keeping) American jobs and competing with China.

Of course it’s political

Don’t blame Biden. Is it a political move? Of course. There’s the timing—months before the elections. There’s the fact that the US hardly imports any Chinese EVs currently anyway. I would even point to the rate they came up for Chinese EV tariffs: 100%, a round, eye-catching number. After the Rhodium Group did a careful analysis of what level of tariffs might be needed to protect Europe’s auto market (they estimated a 40-50% range), Biden goes ahead and slaps a number so high that it comfortably clears the bar as an effective ban on Chinese EVs. In other words, Biden’s Chinese EV ban is clearly and deliberately overkill. Trump responded by saying he would put a 200% tariff on Chinese cars made in Mexico, but at that point the number is so high it doesn’t make a difference.

So it’s a political move. But this is, at least in my understanding, how democracy is supposed to work: politicians try to win elections by enacting policies they think voters like. You might complain that the system is broken—I think it is in many ways—but this is the political reality Americans face. If you lose elections or lose political support for decarbonization policies, then the prospects for an American clean energy transition are far more bleak. Paul Krugman puts it well here:

Given the existential threat posed by climate change, the political coalition behind the green energy transition shouldn’t be fragile, but it is. The Biden administration was able to get large subsidies for renewable energy only by tying those subsidies to the creation of domestic manufacturing jobs. If those subsidies are seen as creating jobs in China instead, our last, best hope of avoiding climate catastrophe will be lost — a consideration that easily outweighs all the usual arguments against tariffs.

So will Biden’s tariffs work as a political move? Let’s break it down. For the voters who care a lot about China, there’s no way that Biden can outflank Trump—nor would he want to. For voters who care strongly about climate change, this is a heavy blow, but they would hardly be expected to switch to Trump anyway. They were sacrificed for the cause. Ultimately, the EV tariffs are targeted at voters who are economically tied to the US auto industry, particularly in the swing states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Georgia. A virtual ban on Chinese EVs—as symbolic as it might be—builds on his promises to support the US auto industry, particularly union autoworkers whose recent strike he famously joined in solidarity. (Interestingly, Biden’s speech at the UAW strike almost seemed to deflect blame from China: “Today, the enemy isn’t some foreign country miles away. It’s right here in our own — in our own area. It’s corporate greed.”)

This is quite a remarkable political situation. One could complain that the rest of the country—indeed the rest of the world, given the repercussions for climate change—is being held hostage by auto industry-connected voters in a few Midwestern states. It wouldn’t be the first time—recall the $80 billion federal bailout of GM and Chrysler during the Great Recession. But to paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld’s famous line: “You go to war against climate change with the electorate you have, not the electorate you want.”

Welcome to Galapagos

It’s impressive if you step back and think about it. Yes, some Americans wouldn’t choose to buy Chinese EVs if given the chance. (I’m thinking about the Americans who bought over 1.7 million Ford or GM pickup trucks last year.) But now the vast majority of Americans will never even get the chance to try a Chinese EV, much less buy one. From a consumer choice standpoint, you have quite a stark government intervention that’s all the more extreme given the vast gulf between EV options available today in the US and what could’ve been possible with Chinese EVs, not just on price but also features, such as LIDAR-based safety systems and in-car beds and fridges.

In fact, most Americans will never even know what they’re missing out on. Although FOMO might eventually might trickle in through news reports and social media from Europe and China, there’s a good chance that most Americans will remain oblivious to the fast-changing developments driven by Chinese EVs in the rest of the world. The US auto market already suffers from the “Galapagos effect” of being detached from global trends and drifting off in bizarre directions, like the American obsession with large trucks and SUVs, a result of both policy (see the Chicken Tax) and culture. The Ford F-150 is the automotive equivalent of the blue-footed booby. Cutting off the US market from Chinese EVs could further exacerbate this tendency. I won’t go so far as to compare it to life in formerly communist East Germany where people waited for years to get the one tiny state-made car called the “Trabant” (aka “Trabbi”), but you get the idea.

This whole discussion also reminds me of high-speed rail. If you travel within China, Japan, or Europe, high-speed rail is just part of life. But most Americans have never experienced what it’s like to travel the distance from Chicago to New York in 4.5 hours reaching speeds of 350 km/h (217 mph). Instead, for most Americans, long drives and flights are just part of life. It’s much harder to demand change when you’ve never known anything different.

Tariffs as an industrial policy tool

But does the US have to turn into an automotive Galapagos? Or can tariffs be a tool for allowing a homegrown EV industry to emerge and thrive? There’s a strong history of countries using protectionist measures effectively in the auto sector to give their “infant industries” time and space to grow before being exposed to full-blown global competition.

Japan after World War II famously protected its own nascent auto market. After the war, the Japanese government carefully restricted foreign currency allocations to imported vehicles, which were seen as a “waste” of scarce foreign currency reserves. In addition, Japan placed high tariffs on imported passenger vehicles (40%) and engines (30%). Even though Japan officially joined the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1955 (the precursor to the WTO), it delayed liberalizing its auto market until after 1964 when it joined the OECD. In the run-up to liberalization, Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) pushed Japanese auto companies to make an all-out sprint to improve productivity and ramp up production. The imminent threat of exposure to global competition spurred Japan’s entire auto industry to become competitive in a stunningly short period of time.

South Korea also used strict auto industry protections to give its own big automakers at the time—Hyundai, Daewoo, and Kia—a chance to catch up and eventually export to the US market. Here’s a 1984 Washington Post piece from Seoul:

You must look hard to find an import on the streets of Seoul. The private cars, trucks and smoke-belching buses that crowd alleys and avenues in this city of 9 million people almost all bear the emblems of South Korean manufacturers.

A small but remarkable motor vehicle industry has emerged in South Korea in the past decade, protected by a virtual ban on purchases from abroad. Last year, 221,000 vehicles -- 122,000 of them passenger cars -- rolled off its assembly lines.

Today, the Hyundai-Kia auto group is the third largest carmaker in the world and the second biggest EV seller in the US after Tesla.

China’s auto industry before EVs

The story of the Chinese auto industry is especially interesting. It was viewed for a long time as an industrial policy failure. China had required foreign automakers to set up joint ventures with Chinese state-owned automakers. BAIC partnered with AMC (later Chrysler). SAIC partnered with GM and Volkswagen. GAC partnered with Honda and Toyota. FAW partnered with Volkswagen to make Audis. Incredibly, the partnerships were so tight that Chinese car models “inherited” the particular strengths of their foreign partners, as shown by a really amazing study on industrial policy and tech transfer (which I mentioned in an earlier piece). Chinese automakers that worked with Japanese partners had better fuel efficiency. Chinese automakers that worked with German partners had stronger engine performance.

While Chinese automakers were able to produce millions of cars for the domestic market and cultivate a robust auto parts industry, they never managed to become the Chinese equivalent of a Toyota or Ford on the world stage. Before the age of EVs, most Americans probably couldn’t name a single Chinese car company. Chinese analysts pointed to many factors for this failure. Some argued that China suffered from “large country disease” (大国病) and that the vast size of the country’s protected domestic market made Chinese automakers complacent. (I think I can name at least one other country that might suffer from “large country disease.”) Other researchers I’ve talked to in Beijing point to a lack of technological sophistication from the industry regulator’s standpoint, including personnel at the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). They contrast the failures of China’s traditional auto industry with the country’s successful high-speed rail program, which was overseen and run by career railway engineers, including the railway minister himself (who is now serving a lifetime prison sentence for corruption, which is a story for another day).

All that changed with EV batteries. While consumer subsidies, municipal traffic restrictions, procurement strategies, and many, many other policy tools were crucial in launching China’s EV industry, it was ultimately technological progress in the cost and performance of Chinese EV batteries that made the shift away from internal combustion engines possible. I’ll save the full story of China’s EV industry for another time.

The future of American EVs?

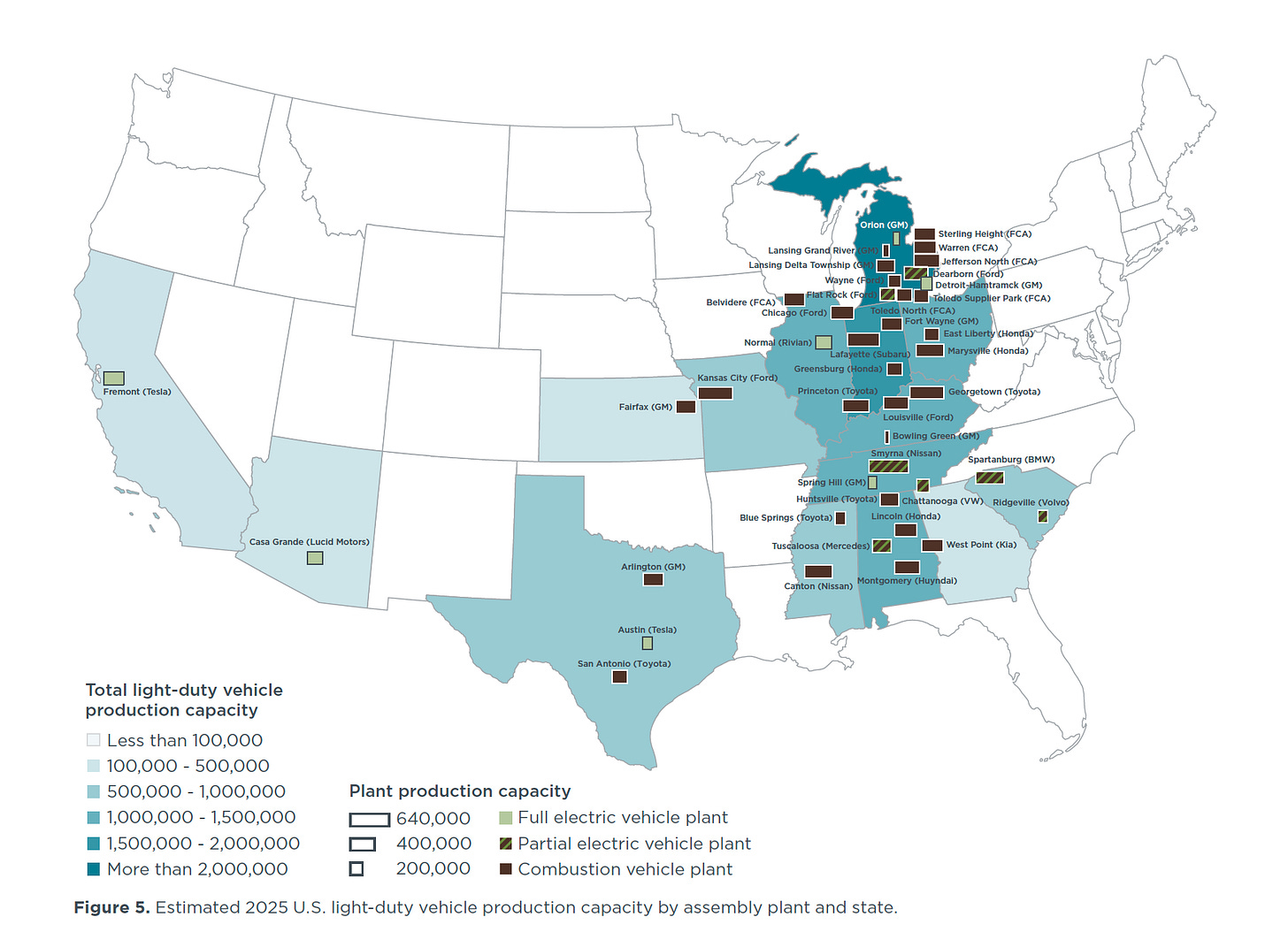

Given all this, what are the prospects for using the protection of tariffs—at least from Chinese EVs—to develop a competitive American EV industry? The picture doesn’t look so good right now. Tesla is currently struggling, with BYD hot on its heels. GM and Ford are both cutting back their EV programs after spending billions of dollars to launch electric versions of their most popular (and most lucrative) models, like the Ford F-150 Lightning. The stocks of EV startups like Rivian and Lucid are trading at a fraction of their peak values. Lordstown Motors filed for bankruptcy last year, and Fisker appears to be on the brink this year.

But I would argue that it’s exactly at this dire moment when US policies should be doubling down on American EVs. I think immediately of the Chinese solar industry, which got a massive demand-side policy boost right when it was facing its darkest period with the Global Financial Crisis and trade backlash from the US and Europe, as I mentioned in another piece.

And there are reasons for optimism. The IRA has already made great strides in boosting battery manufacturing in the US. Here’s just a small sample of battery plant announcements I jotted down from TechCrunch:

September 2021 – Ford and SK On JV called BlueOval SK – 2 battery plants in Kentucky, 1 in Tennessee, 2023 LFP BlueOval Battery Park Michigan with CATL, $3.5 billion

October 2022 – BMW and AESC $1.6 billion, 30 GWh battery plant South Carolina

August 2022 – Honda and LG North America JV – Ohio

December 2022 – GM and LG Chem – JV Ultium Cells $2.5 billion loan from US government

March 2023 – Stellantis and Samsung SDI – Indiana

April 2023 – GM and Samsung SDI $3 billion battery plant, 30 GWh

April 2023 – Hyundai and SK On - $5 billion battery plant, Georgia

May 2023 – Hyundai and LG JV battery cell plant near Savannah, Georgia

July 2023 – Stellantis and Samsung – second factory in Indiana

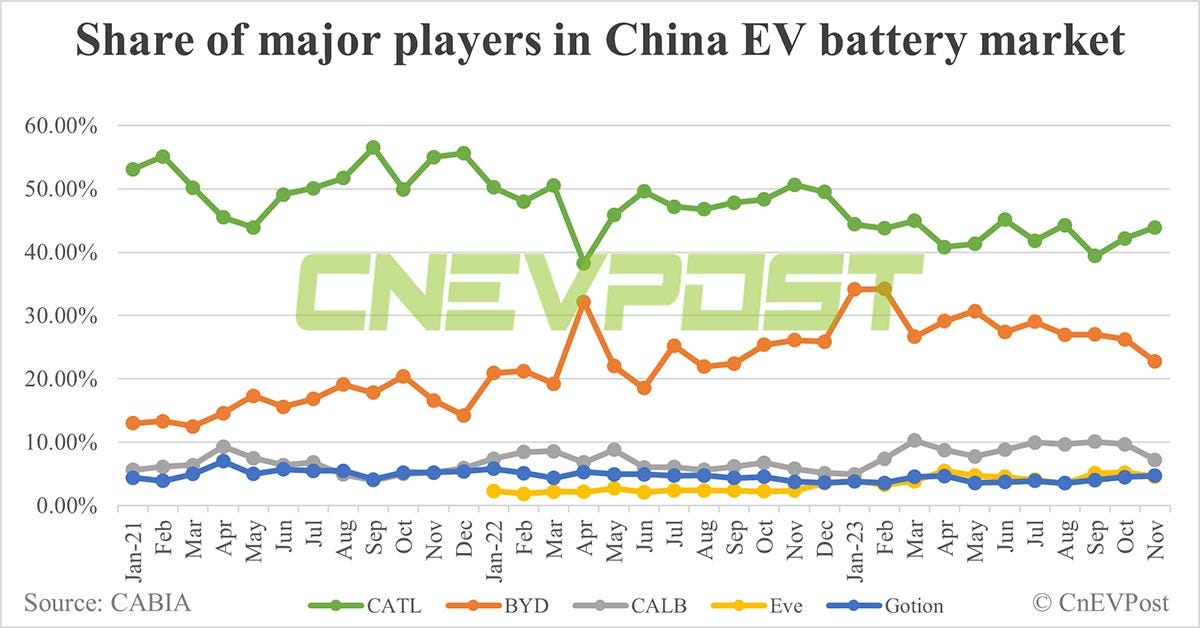

Rapid changes in technology can also offer opportunities for once-dominant players to be dethroned. An example of this is the shift in the EV battery market within China, pictured in the chart below. CATL (green line) has long been regarded as the unassailable EV battery leader in China and globally. But with a broader industry shift to LFP batteries, BYD (orange line) has been slowly gaining market share over the past few years. The point here is that the EV industry is changing so quickly that new technologies from new battery chemistries to new manufacturing techniques like gigacasting can present opportunities for outside challengers. China’s dominance in EV battery technology is far from guaranteed. Moreover, American EV makers can also capitalize on partnerships with EV battery makers outside of China, including Samsung SDI, SK On, LG Chem, and Panasonic.

A key factor in all this is creating a sense of urgency. Japan and South Korea both faced pressure to eventually remove their protectionist walls and let their automakers be exposed to global competition. This is not the case so far with the latest Biden tariffs, which have no sunsetting timeline. Even with the challenge from Japanese automakers in the 1970s and 1980s, while US automakers got some breathing room through a tough trade deal with Japan that including “voluntary” restraints on Japanese exports, US automakers knew that they would need to get their act together soon to face Toyota, Honda, and Nissan when they set up plants in the US. It doesn’t seem like the US is open to Chinese automakers moving production to the US anytime soon (although Trump seemed to express some openness to the idea to my surprise: “If they want to build a plant in Michigan, in Ohio, in South Carolina, they can, using American workers, they can”).

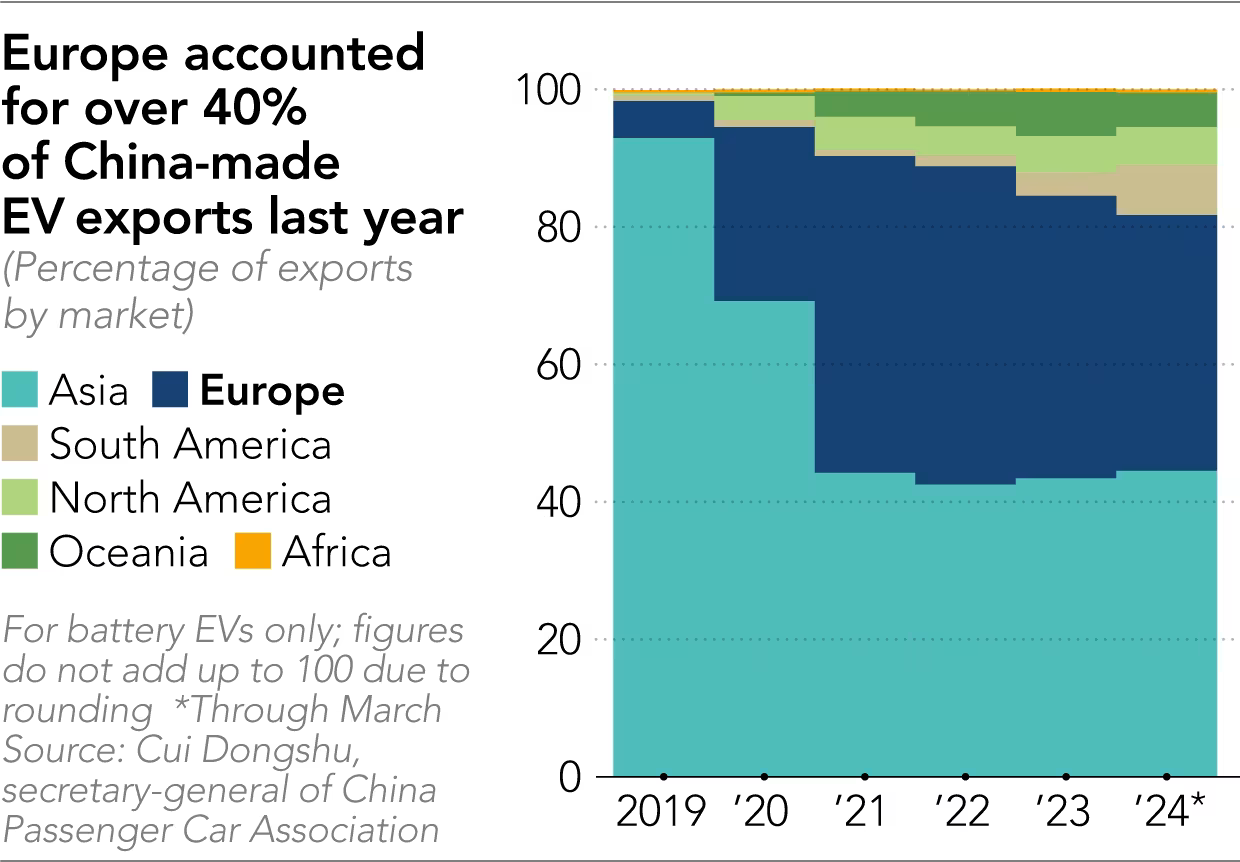

Europe at this very moment is showing an alternative path to dealing with Chinese EVs. Some EU leaders have already pushed back on Biden’s tariffs, including German Chancellor Olaf Scholz: "Protectionism only makes everything more expensive in the end…What we need is fair and free global trade.” While European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has been talking tough on Chinese overcapacity and tariffs, individual EU countries such as Spain, Germany, and of course Hungary (which has a particularly close relationship with China) have been busy setting up joint production with Chinese EV and battery makers. During Chinese President Xi Jinping’s recent visit to France (where he brought along a delegation of Chinese EV executives), French President Emmanuel Macron said, “We want to welcome more Chinese investors to France.” Stellantis just announced a partnership with China’s Leapmotor to sell Chinese EVs to nine European countries. By working with Chinese EV firms and Chinese suppliers, European automakers could get an edge over US automakers that shun—or are shut out of—Chinese EV technology and supply chains.

NUMMI

I’ll end with the story of the NUMMI auto plant, which offers both hope and a warning about the US auto industry’s ability to transform itself. The rise of Japanese automakers in the 1970s and 1980s put tremendous pressure on the Big Three US automakers to find a way to compete. GM was forced to close its struggling Fremont plant in 1982, laying off thousands of workers. The plant had been widely regarded as the worst in the industry where drugs, alcohol, and absenteeism were rampant. This is from This American Life’s incredible two-part podcast series on the NUMMI plant:

Jeffrey Liker

One of the expressions was, you can buy anything you want in the GM plant in Fremont. If you want sex, if you want drugs, if you want alcohol, it's there. During breaks, during lunchtime, if you want to gamble illegally-- any illegal activity was available for the asking within that plant.

Frank Langfitt

Sounds like prison.

Jeffrey Liker

Actually, the analogy to prison is a good analogy, because the workers were stuck there because they could not find anything close to that level of job and pay and benefits at their level of education and skill. So they were trapped there.

And they also felt like we have a job for life, and the union will always protect us. So we're stuck here, and it's long term. And then all these illegal things crop up, so we can entertain ourselves while we're stuck here.

Rick Madrid

A lot of booze on the line. I mean, it was just amazing. And as long as you did your job, they really didn't care.

Frank Langfitt

What kind of booze? What were people drinking?

Rick Madrid

Whiskey, gin.

GM then reopened the plant in 1984 as a joint operation with Toyota called New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI). It showed that US automakers were willing to get over their pride and complacency and actually learn from their Japanese rivals. GM workers traveled to Japan to work side-by-side with Toyota factory workers, learning Japanese manufacturing techniques and Toyota’s famous process of kaizen (aka continuous improvement). Again, from This American Life’s two-part series:

Jeffrey Liker

And they spent about two weeks, and they worked in a Toyota plant.

John Shook

Hooked up at the hip with a counterpart in the Corolla plant, someone who did the exact same job you'd be doing back in Fremont.

Jeffrey Liker

And they start to do the job, and they were pretty proud, because they were building cars back in the United States. And they wanted to show they could do it within the time allotted, and they would usually get behind, and they would struggle, and they would try to catch up. And at some point, somebody would come over and say, do you want me to help?

And that was a revelation, because nobody in the GM plant would ever ask to help. They would come and yell at you because you got behind.

John Shook

Really, we wanted to give them a chance to see and experience a different way of doing things. We wanted them to see the culture there, the way people worked together to solve problems.

NUMMI was ultimately closed in 2010 after GM filed for bankruptcy during the Great Recession. Then, in one of the most symbolically meaningful shifts in the industry’s history, the plant was sold to Tesla and transformed into the Tesla Fremont Factory.

What this story tells me is that US automakers can change, albeit slowly and under tremendous pressure. But at the same time, the problems they face might run far deeper than just technology and equipment.

The best western EVs of tomorrow will come from the parts of the west most open to Chinese EV exports today — that is fundamentally how knowledge transfer works.

Depressing story.

Democracy's broken. Capitalism's broken. Americans don't have a clue what's going on in the rest of the world.

As a result, millions more will die from climate change.