China's Faustian bargain for foreign firms

Why do foreign companies agree to work with China and build up their future Chinese competitors?

(This piece builds on my expert testimony for the U.S.-China Commission and on a previous piece on how China uses foreign firms to “turbocharge” its own industries.)

The Faustian bargain

In my recent expert testimony before the U.S.-China Commission, I said: “Foreign firms agree to a Faustian bargain where they profit from selling to China’s market in the near term but build up their future Chinese competitors in the long run.”

I was pointing out a pattern where foreign companies, often drawn in by China’s vast market, basically agree to help China develop its domestic industries. Foreign companies agree to build manufacturing plants in China, form joint ventures with Chinese companies, set up R&D centers, share technology and production techniques, and even sell off parts of their business.

This is a deliberate strategy by China to use foreign firms to upgrade China’s tech-industrial ecosystem, as I’ve previously written about. Over time, China pushes these foreign firms to share more technology and use more Chinese suppliers. Foreign companies end up training a whole cohort of Chinese engineers and managers who can later help Chinese companies or even launch new startups.1

Time and again, foreign firms start with a useful partnership but end up helping to grow their most formidable competitors. Noah Smith calls this the “China cycle.” I mostly see this as part of the classic industrial policy playbook used by East Asian countries like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The difference, however, is China’s scale.

As Chinese firms become competitive, foreign companies get hit with a one-two punch. First, they’re squeezed out of the China market, losing a major source of revenue. Then they’re challenged in markets outside of China. This is what’s happening now with the global auto industry, as industry veteran Michael Dunne has written about. American, German, and Japanese automakers are watching their lucrative China businesses collapse while also losing share to Chinese competitors in other markets.

Why do foreign companies keep doing this?

If this keeps happening again and again, then why do foreign companies keep working with China, knowing they may be sowing the seeds of their own destruction?

Market access

A major pull factor is of course access to China’s large and growing domestic market, access that China makes conditional on localizing production in China and sharing technology. “Market access in exchange for technology” (市场换技术), as I’ve written about before.

Many foreign firms have made a fortune in China. Apple has made a whopping $227 billion in operating profit in China over the past 10 years alone, accounting for over a quarter of its operating profit during this period. Volkswagen has made over €54 billion in operating profit in China over the past 15 years. GM made over $17 billion in profit in China from 2012 to 2023 alone. Profits from their China businesses have been a lifeline for many of these companies in their darkest hours, like the 2008 financial crisis for GM and the 2015 emissions scandal for Volkswagen.

In many cases, foreign companies have entered into this Faustian bargain with their eyes wide open. From a 2007 Wall Street Journal article titled, “GM’s Chinese Partner Looms as a New Rival”:

GM says the bargain it made -- access to the Chinese market in exchange for transferring technology and expertise -- was worth it. "We made a big bet back in 1997, and it's paid off for us very well," says Chief Executive Rick Wagoner.

Low-cost manufacturing base

Another major pull factor is being able to use China as a low-cost manufacturing base. Even before the official start of reform and opening up in 1978, US businesses were already starting to import clothing and textiles from China to take advantage of China’s low labor costs, as documented in Elizabeth Ingleson’s book Made in China. In 1984, American Motors Corporation (AMC) formed the first automotive joint venture in China with state-owned Beijing Automotive Industry Corporation (BAIC), aiming to use China’s low labor costs to make jeeps that could compete with Japanese automakers.

In the decades since, waves of foreign firms outsourcing production to China have helped transform the country into a manufacturing powerhouse. This in turn has made China even more attractive as a manufacturing base for foreign companies, creating a self-reinforcing feedback loop.

In some cases, working with China is an existential move for these companies. Would the iPhone exist today if it weren’t for Apple and Foxconn’s incredibly nimble and efficient factories in China? Would Tesla exist today if it weren’t for the launch of its Shanghai Gigafactory, which now produces over half of its cars? It was exactly during this time when Elon Musk himself said that Tesla was a month away from bankruptcy. A New York Times headline captures it perfectly: “A Pivot to China Saved Elon Musk. It Also Binds Him to Beijing.”

Technological hubris

At the same time, foreign companies are often overconfident. They think they could reap the benefits of a Chinese partnership but always stay a few steps ahead. They agree to share some technology and know-how but believe they can keep their cutting-edge core technology out of Chinese hands.

For bullet trains, Siemens has always insisted they never shared core technology, like software. For solar, polysilicon makers like Germany’s Wacker and America’s GT Advanced Technology tried to avoid licensing their most advanced technology to Chinese companies.2 For telecom equipment, foreign equipment makers thought they could have their cake and eat it too. From Eva Dou’s book House of Huawei:

Former Canadian ambassador Guy Saint-Jacques recalled Canadian companies being confident that they can stay a step ahead by transferring only older generations of technology while enjoying the sales bonanza. “I always compare this to running toward a cliff. At some point, you will fall down,” Saint-Jacques said.

Eventually, Chinese firms like CRRC, Tongwei, and Huawei came to dominate each of these industries.

Foreign companies frequently doubt China’s ability to produce real global competitors.

GM shared some of its electric car technology with its Chinese partner SAIC in the early 2010s after launching the Chevrolet Volt. According to reporting by Keith Bradsher, “Executives at Volkswagen, Ford and other automakers had long warned that G.M. was sharing too much advanced technology with SAIC.” Industry veteran Bill Russo said it wasn’t just GM: “Everyone among the foreign automakers had a condescending, arrogant attitude toward the capability of the Chinese companies to embrace innovation.”

When Ford’s CEO Jim Farley visited China in 2023 for the first time since the pandemic, he was shocked by the impressive quality of electric cars made by their longtime Chinese partner, state-owned Changan Automobile. His CFO who had joined him on the trip said, “These guys are ahead of us.” Farley later had a Xiaomi SU7 shipped from China to the US and has been driving it ever since.

The most infamous example now is Elon Musk’s 2011 Bloomberg interview where he laughs when BYD is mentioned as a potential rival to Tesla and says, “Have you seen their car?” When Tesla built its Shanghai factory, it worked with Chinese suppliers and helped to upgrade China’s EV industry. Fast forward to 2024 when Elon Musk said that Chinese EVs would “pretty much demolish most other car companies in the world” without trade barriers in place. BYD is now the world’s largest EV company and Tesla’s biggest competitor.

In some ways, these foreign firms could be forgiven for merely extrapolating from their experiences with similar joint ventures and localization efforts in other developing countries, like Brazil, India, and Indonesia. Even in China, these partnerships might not yield a real Chinese competitor for years, which is what happened in the auto industry. But over time, China has been focused on trying to absorb and build on top of foreign technology across a range of industries, in a process known as IDAR (introduce, digest, assimilate, re-innovate; 引进消化吸收再创新).

Selling off assets

In some cases, foreign firms sell parts of their business to China when they’re going through a restructuring or trying to sell off old technology. This creates a perfect opportunity for Chinese firms to gain new technology.

In the 1990s, GM went through a restructuring to streamline its business and sold off its rare earths magnet division. The buyer ended up being a group closely tied to Beijing. From Ernest Scheyder’s book The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives:

In an ironic twist, GM once was a global leader in the rare earths magnet industry through its Magnequench division. But in 1995, GM agreed to sell the division and its patents to a consortium that included two Chinese partners, including one led by the son-in-law of the former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping.

The Magnequench deal helped GM sell more cars in China but also gave China access to the rare earths magnet technology that had first been developed in the United States…

This magnet technology is used to make everything from electric motors and data storage devices to precision-guided munitions. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) approved the sale on the condition that Magnequench continue to operate in the US and employ American workers for five years. But when those five years were done, Magnequench’s US operations were shut down and its equipment was moved to China.

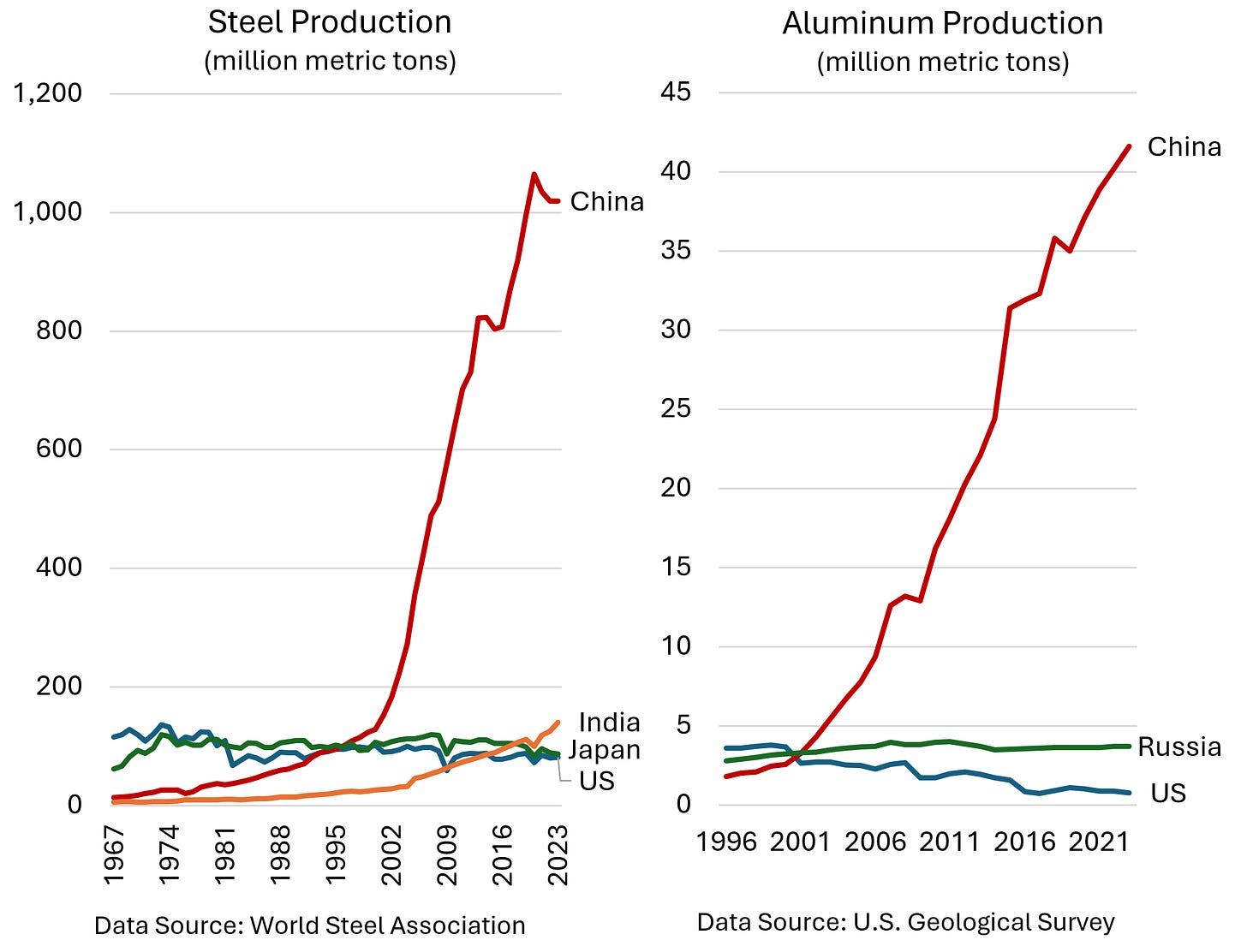

In the 1990s and 2000s, Western and Japanese steel, aluminum, and magnesium companies like Germany’s ThyssenKrupp and Norway’s Norsk Hydro faced economic pressure to close down mills and smelters. Chinese companies like Shougang bought up these metal plants at fire-sale prices, shipped all the equipment back to China, and reverse-engineered the technology (see this fascinating CSIS report). In the case of one struggling ThyssenKrupp steel plant in Germany, China’s Shagang Group bought the plant and shipped 250,000 tons of equipment and 40 tons of technical manuals back to China. These Western and Japanese companies were glad to get some money for their shuttered plants while Chinese companies got a great deal on equipment and technology.

More recently, in 2016, AMD sold its chip packaging facilities in China and Malaysia to Tongfu Microelectronics, a Chinese contract chip manufacturer. AMD had been selling off its manufacturing facilities ever since it decided to become a “fabless” chip designer in the 2000s and spun out GlobalFoundries in 2009. Since then, AMD has relied on Tongfu for advanced packaging and testing, including most recently for its cutting-edge MI300 AI chips. Tongfu’s acquisition of these facilities and its partnership with AMD helped enable it to move into high-bandwidth memory, a crucial component of AI chips.

Another recent example is LG Display. Last year, LG Display announced it was selling off its two LCD factories in Guangzhou to China’s TCL Technology in order to focus on more cutting-edge OLED technology. This has allowed TCL to boost its share of global LCD production capacity from 20% to 25%. Through TCL and its rival BOE, China will have over 50% of the global capacity for LCD production.

Making foreign firms work for China

To end, I’ll share a story that shows how determined China is to get the most out of partnerships with foreign firms. It’s the story of Silicon Valley Bank (yes, the one that collapsed in 2023) and its struggle to get into the China market, based on former CEO Ken Wilcox’s book The China Business Conundrum.

In the 2010s, Silicon Valley Bank was courted by Chinese officials who wanted them to set up a banking business in Shanghai based on their unique model of lending to tech startups and VC firms. Silicon Valley Bank tried to do everything right: they learned Chinese, developed high-level contacts with the Shanghai government including its party secretary, and set up a 50/50 joint venture with the city’s biggest bank, Shanghai Pudong Development Bank.

But they constantly ran into issues with getting licenses and then were told they would have to wait three years before they had permission to handle RMB currency—meaning they effectively couldn’t do anything. In the meantime, they were pressured into teaching their business model to a bunch of Chinese banks. By the time they were allowed to operate, their JV partner Shanghai Pudong Development Bank had already copied their business model and turned into their competitor.

As Wilcox says in an interview, their Chinese partner didn’t really care about the joint venture per se. “They cared about whether or not they learned things from us that they could use.”

A great example is China’s telecom equipment industry. See: Eric Harwit. 2007. “Building China's Telecommunications Network: Industrial Policy and the Role of Chinese State-Owned, Foreign and Private Domestic Enterprises.” The China Quarterly.

Fang Zhang and Kelly Sims Gallagher. 2016. “Innovation and Technology Transfer through Global Value Chains: Evidence from China’s PV Industry.” Energy Policy.

Let me revise to properly reflect your direct perspective in those final points:

1. While mandatory joint ventures can theoretically assist in national technology upgrading, their role in explaining China's current corporate leaders is questionable.

2. The success stories of firms like CATL, BYD, Huawei, and Deep Seek seem to follow more conventional paths to technological advancement. CATL, for instance, acquired technology through straightforward means - licensing from American universities and recruiting experienced Japanese engineers who faced career stagnation in their home country. This hardly fits the narrative of state-directed technology acquisition.

3. China's current competitive advantage in electronics manufacturing did receive state support, but primarily through broad-based policies like Free Trade Agreements rather than targeted industrial policy. The sector's development appears relatively market-driven.

4. The limitations of state-directed development become apparent in sectors like semiconductors and aerospace. Despite earlier entry into semiconductor manufacturing than Taiwan, China still lags behind. In aerospace, China hasn't matched even Brazil's capabilities, let alone Western leaders.

5. You're probably more knowledgeable than me on this subject. Perhaps the companies I mentioned did use the joint strategy to acquire technology by leveraging their relationship with government. More specific case studies would be much appreciated.

6. Also I think that the western firms are not being arrogant in thinking that the Chinese can't copy them that well. I'm from Bangladesh and many international banks have been operating in the country since the British Raj days and currently largely employ locals. However these international banks are still far more productive than local private banks.

Why do foreign companies agree to work with China?

Because if they didn't, their competitor would and tech transfer would have happened AND they would have lost out on profit.

This is the fundamental difference between US's free market capitalism and China's state capitalism.

Imagine if each Chinese company had been allowed to decide what stake to offer in a joint venture, one company would offer 49%, then the next would give 55%, then 60%, then 80%. Instead, the Chinese state stepped in and said the maximum stake you're allowed to offer is 49%, every Chinese company can point to that and say my hands are tied.

What about the reverse? Could American companies have recognized the looming threat of Chinese cars and all the big mfgs sat down together and agreed upon what tech not to transfer to China and how they would punish each other if they defected? Actually, no. Even just sitting down in a room together to discuss this would have been illegal as this is collusion and a violation of the tenets of free market capitalism. The only way company CEOs can legally sit down and talk about any issue is if the government invites them to sit down and agree together, with the force of law backing it. And the US government had no appetite or capability to do this during the bulk of China's rise.

After decades of poo-poohing industrial policy as a concept, America is now finally on the industrial policy bandwagon except not acknowledging that it took China decades of lessons before learning how to do industrial policy semi-competently and expecting it to be a slam dunk from the start. As soon as the first Solyndra-style debacle happens, America will back out of industrial policy again for another few decades.