China's emerging export control regime

China is trying to build a "unified export control system" that's about much more than just leverage in the latest negotiations with the US

China recently announced a sweeping expansion of its export control framework that has caused shock and concern in the US, Europe, and around the world. The most striking part was MOFCOM’s No. 61 announcement establishing extraterritorial jurisdiction over any product made anywhere in the world containing at least 0.1% rare-earth material from China by value. This is the Chinese analog to the US Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) in its extraterritorial reach and the US “de minimis rule” in its broad content-based scope.

Why did China do this? Some argue that this is China’s effort to build leverage in the run-up to a potential meeting between Trump and Xi at APEC. Others argue that this is China’s effort to firmly push back against what it views as a series of US actions that violated the truce following the talks in Madrid (what Cameron Johnson has called a “brush-back pitch”). This view is supported by recent comments from MOFCOM complaining about US actions after Madrid that “severely harm China’s interests” (严重损害中方利益), including the expansion of the US Entity List to affiliates with 50% or more ownership by a listed entity and the imposition of port fees on Chinese ships.

While these explanations are all valid, I would also point to another underlying motivation: China wants to build a robust export control regime to preserve and leverage its unique technological and industrial capabilities. The recent series of export control-related announcements from MOFCOM are but the latest developments in China’s efforts to create what it calls a “unified export control system” (统一的出口管制制度). While recent US actions or upcoming negotiations between the two countries may have accelerated China’s efforts, China’s latest moves are ultimately part of a long-term push to build up an export control system that can fulfill a number of strategic goals:

Geopolitical leverage: developing tools of economic coercion to use against other countries

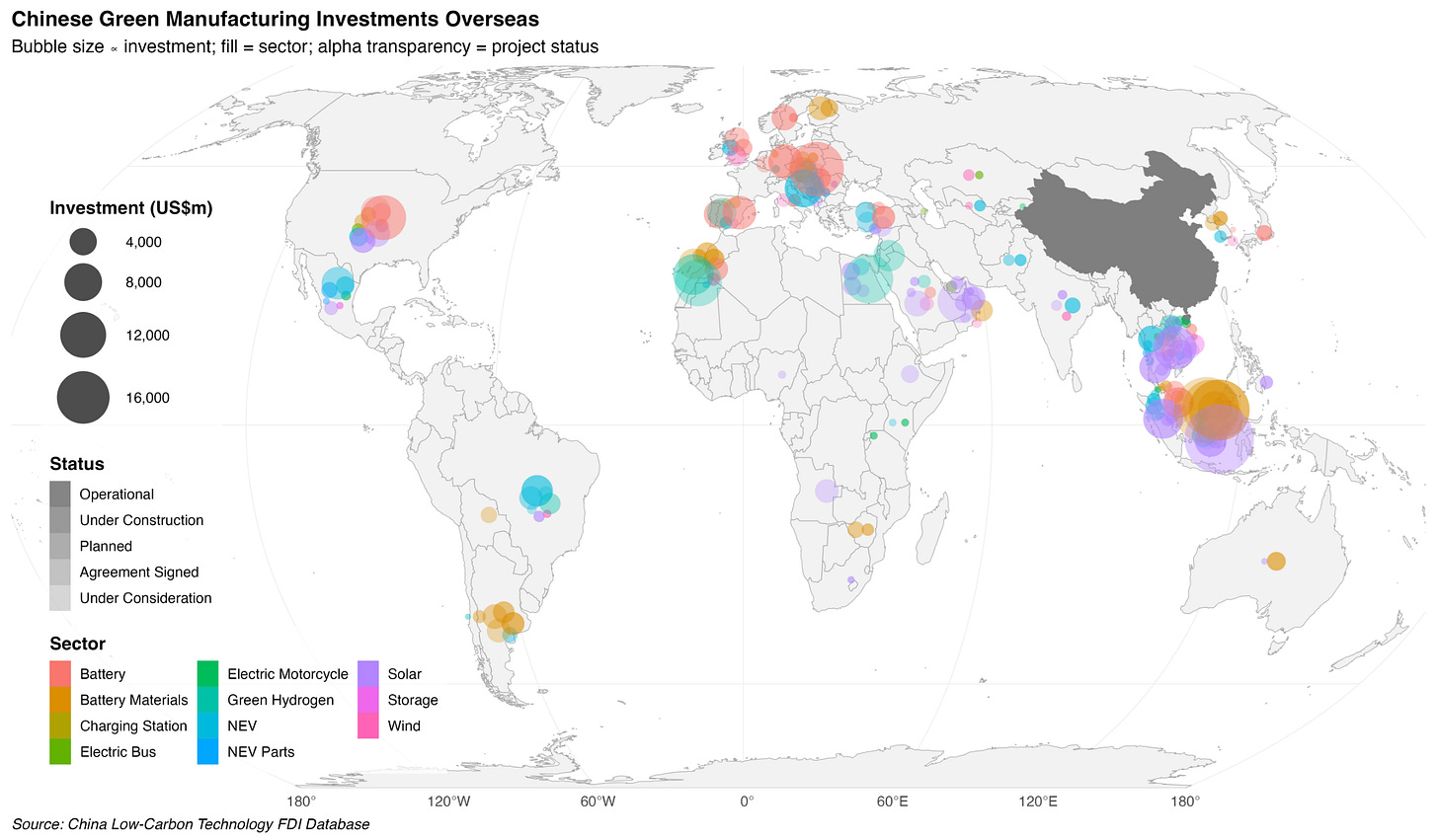

Technological control: retaining China’s technological edge in certain industries, like EV batteries, particularly as Chinese firms expand production overseas

National security: controlling military and dual-use items that can be used by potential adversaries

Building an export control system

For years, China had fragmented export controls on military items and materials for nuclear weapons overseen by a patchwork of agencies. During the 1980s and 1990s, China began to build a more legally-grounded system of export controls for a range of military and “dual-use” items, particularly around weapons of mass destruction. Ironically, it was the US and other international actors who pressed China to establish a more robust system of export controls (see Evan Medeiros’s 2005 RAND report). In 2001, China published its first catalog of export-controlled items (中国禁止出口限制出口技术目录). In 2010, China reportedly restricted rare earths exports to Japan in retaliation for the detention of a Chinese fisherman around the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. (Some researchers at ANU and IMD Business School have questioned whether rare earth exports to Japan were in fact limited; Seaver Wang provides a strong case that they indeed were.)1

But over the past decade, two major changes have driven China to move faster to develop a more comprehensive and institutionalized export control system.

First, a series of US export control shocks starting in 2017 prompted China to hone its own tools for economic retaliation. In March 2017, the US placed a suspended “denial order” on ZTE for violating US sanctions on Iran and North Korea. The US denial order would have effectively cut off ZTE from all US components for up to seven years but was initially suspended as part of a deal. When the US actually activated the denial order on ZTE a year later, it quickly brought the Chinese tech champion to the brink of collapse.

The March 2017 ZTE case was a wake-up call for Beijing, demonstrating that the US was willing and able to use export controls to effectively shut down a major Chinese company. Not long after in June 2017, MOFCOM circulated a draft Export Control Law that established a legally-grounded, unified system of export controls. In 2019 and 2020, the US tightened export controls on Huawei, essentially cutting it off from US technology and from TSMC’s chip fabrication services. Not long after in late 2020, China fast-tracked the final approval of the Export Control Law.

Second, China’s technological and industrial capabilities have evolved to a point where Beijing now deems them worth controlling for geostrategic and trade reasons. China now believes that it has technological superiority or unique production capabilities in areas such as rare earths processing, permanent magnets, LFP cathodes for batteries, and lithium extraction. This gives China geostrategic leverage. And it also means China has something valuable to safeguard. As Chinese companies like BYD and CATL build manufacturing plants abroad, export controls allow Beijing to ensure that Chinese companies don’t sell or give away cutting-edge technology.

Mirroring the US

Many of China’s actions deliberately mirror aspects of the US system of sanctions and export controls: entity lists, 50% affiliate rules, FDPR extraterritoriality, “de minimis” content rule, technical thresholds for semiconductor manufacturing, “dual use” justifications. This extends beyond export controls. In response to US port fees on Chinese ships, China retaliated with port fees on US ships. In response to US tariffs, China retaliated with similar levels of tariffs. The US conducts backdoor security investigations into Chinese telecom equipment and port cranes; China conducts backdoor security investigations into American IT equipment and Nvidia chips.

At a tactical level, this mirroring is about trying to show that China can not only retaliate against the US but can do so in a way that matches US actions. It also provides political cover. The logic of mirroring means that no one can accuse China of overstepping because China is merely copying the US. At least, that’s what Beijing thinks.

But there’s a deeper strategic motivation here. China sees export controls as important tools for an advanced nation in an age of geopolitical competition. Having been on the receiving end of US export controls, China fully appreciates their strategic value. If the US has a sophisticated export control regime that it can use for geostrategic leverage, then China believes that as a “great power” it should have the same. Export controls are like having a blue-water navy. When Beijing talks about its own export controls, it tries to frame them as “standard international practice” (国际上通行的做法) rather than as any special kind of economic weapon.

But this is not how the US or the rest of the world sees it. The US sees China’s latest export controls as escalatory rather than proportionate. Trump reacted by saying that China was “becoming very hostile” and that its actions held the world “captive.” US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent later said that “this is China versus the world.” EU trade chief Maros Sefcovic said that China’s rare earths export controls were “causing real economic harm and undermining trust” in Europe. For Europeans, China’s actions on rare earths have validated their “de-risking” strategy. Japan, the EU, and other G7 countries have called for a coordinated G7 response to China’s actions.

Beijing was clearly caught off guard and had to make a number of clarifying statements over the following days. MOFCOM had to repeatedly state that these were “export controls not export bans” (“我想强调的是,中国的出口管制不是禁止出口”) and that the estimated impact on global supply chains would actually be very limited (“确信相关影响非常有限”). But the damage to China’s self-described image as a “responsible great power” (负责任大国) and upholder of global stability is hard to undo. What China saw as another step in developing its capacity for export controls—no further than anything the US had done—other countries saw as a highly disruptive act for the global economy.

Blunt vs. precise export controls

Part of the problem is the nature of China’s export controls themselves. Compared with the US, China’s export controls are relatively new and underdeveloped. It’s one thing to have powerful export controls that can send shockwaves throughout the global economy. It’s another thing to have export controls that can be deployed and enforced in a way that’s targeted, precise, and robust. It’s not enough to have economic nuclear bombs; you want the geoeconomic equivalent of long-range precision-guided missiles. Until now, there’s been too much focus on the “what” of export controls and not enough on the “how.”

US export controls are more developed not because they have a bigger impact but because the US has greater institutional capacity for selectively targeting specific countries and individual entities. For all the reports of leaky US export controls on Nvidia GPUs to China, the United States’ ability to enforce export controls on China at such a fine-grained level is a testament to how developed US capabilities are in this area. For all the effort to mirror the US, China’s export controls are very different in important ways that cause additional disruption and distrust.

China’s export controls are fairly blunt. Earlier this year when China first implemented its rare earths export controls, it essentially placed a blanket ban on large swaths of rare earths-related exports and then gradually sifted through a vast number of applications to review and grant licenses on a case-by-case basis. This process created a massive backlog of pending applications and caused a host of supply chain issues as international buyers waited for approval. Now China plans to do the same for almost any product that contains virtually any Chinese rare earths on the restricted list. This is a blunt approach that forces many legitimate end-users to go through a long approval process to obtain critical components they had already been using.

China is trying to do export controls on the cheap. The US has BIS Office of Export Enforcement agents positioned around the world to conduct investigations into potential violations of US export controls. Because China doesn’t have the same globe-spanning capabilities for monitoring and enforcement, it has to rely on more indirect methods, such as detailed self-reporting by buyers seeking a license. Here’s the EU trade chief Maros Sefcovic again talking about the ordeal that companies have to go through:

“Companies filling out these applications tell us that they are often asked questions that even national authorities in EU member states would not need. Often, they must provide very detailed photo documentation of production line processes, as well as information on their entire supply chain.”

This is a very cumbersome way of doing export controls, not just for foreign companies seeking licenses but also for authorities back in Beijing that have to sift through all this documentation and make a case-by-case determination. Reviewing all this documentation requires technical expertise on top of sheer bureaucratic manpower. Moreover, Chinese authorities are likely to err on the conservative side, particularly if they want to prevent potential stockpiling or workarounds. This is likely one key reason for the bureaucratic delays in license approvals that caused so much supply chain turmoil earlier this year.

China is trying to retain maximum optionality. China’s export control rules are crafted in a broad way that provides Beijing with significant discretion over how to determine “dual use” and “end use.” Beijing can turn the knobs on specific countries, companies, and items, ranging from an outright ban to no ban at all to everything in between. Beijing can also change these policies loudly or quietly, leaving other countries guessing.

But ironically by making the process so broad and opaque, Beijing creates a lot of extra uncertainty and causes other countries to fear the worst. Other countries are left wondering whether they’re being punished in some way or if delays are just the result of bureaucratic backlogs (see, for example, “Delays by Design?” by MERICS).

China’s expanding geoeconomic toolkit

Finally, it’s important to see China’s emerging export controls as part of China’s growing geoeconomic toolkit. Some of it is borrowed from the US, but some of it is distinctly Chinese. Here’s a sample of cases where China has deployed geoeconomic tools in retaliation for unwanted actions by foreign countries:

South Korea: In response to the positioning of US THAAD missiles in South Korea in 2016, China began a pressure campaign targeting Korean businesses in China, Korean exports to China, and Chinese tourism to South Korea.

Lithuania: After Lithuania changed the name of its “Taipei Representative Office” to “Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius” in 2021, China retaliated by expelling Lithuanian diplomats, banning Lithuanian imports, and generally running an economic pressure campaign on the small Baltic state.

Norway: The decision to award the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 to Liu Xiaobo, a well-known activist for Chinese democracy, led to China retaliating against Norway by banning imports of Norwegian salmon and other products.

Australia: In 2020, after Australia pushed for an investigation into the origins of COVID-19, China retaliated by placing tariffs or bans on a wide range of Australian imports, including coal, wine, beef, and barley.

Taiwan: After Tsai Ing-wen’s election victory in 2016, China ramped up pressure through a range of measures, including by restricting mainland tour groups and individual travel.

In addition to “negative” coercive or punitive measures, China also uses economic “carrots” like the possibility of Chinese investment to influence the actions of other countries. The latest version of this is China’s steering of outbound manufacturing investment toward favored countries through what I’ve called “industrial diplomacy.”

While in the past China has relied more on access to its large market for geopolitical leverage, such as import bans and pulling back tourism, export controls mark a shift toward using technology and industrial capacity as geopolitical tools. Ironically, the US and China are borrowing from each other. The US is now using its large market as a geopolitical tool while China is following in US footsteps with the formation of its own export control regime. Whatever direction US-China negotiations take, China is likely to continue building up its export control system.

This line was updated on October 21, 2025 thanks to a helpful thread from Seaver Wang.

Give China a few years, and they will develop an export control more robust, and effective than USA. If there is one thing, I have learned reading about China, they actually tend to learn from their mistakes. On the contrary, post- 2016 Washington's policy has been one of flip-flop, and now it has been reduced to the whims of God-Emperor Trump.

No no, you got it wrong. China wants to prevent RE from being used by US military to attack China. That is sufficient explanation. Apply Occam’s razor. All other motives you imply into China is just projection. 😀